The Internet’s Physical Backbone: Undersea cables, data centers, and IXPs

The Internet’s Physical Backbone: Undersea Cables, Data Centers, and IXPs

Introduction: The Myth of the “Cloud”

The internet is often conceptualized as an ethereal “cloud”—a weightless, invisible realm where data floats freely. In reality, this global network rests on an astonishing physical infrastructure spanning continents and oceans, consuming immense energy, and requiring constant human maintenance. This tangible framework—comprising submarine cables crossing ocean floors, humming data centers consuming small cities’ worth of electricity, and unassuming buildings where networks exchange traffic—forms the actual backbone of our digital world.

As Andrew Blum articulates in Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet: “The Internet is not a cloud. It’s a collection of physical places connected by physical wires.” This article provides a comprehensive examination of the three pillars of internet infrastructure: undersea cables that connect continents, data centers that house our digital lives, and Internet Exchange Points where networks meet.

1. Undersea Cables: The Transoceanic Arteries

1.1 Historical Evolution: From Telegraph to Terabits

The Victorian Internet (1850s-1950s):

First transatlantic telegraph cable (1858): Failed after weeks, but proved concept

Global telegraph network by 1900: 200,000 miles of submarine cables

Key difference: Point-to-point connections vs. today’s shared fiber infrastructure

The Communication Revolution (1956-1988):

TAT-1 (1956): First transatlantic telephone cable (36 voice channels)

Coaxial cable era: Gradual increases in capacity

Satellite competition: 1960s-1980s saw satellites as primary transoceanic solution

The Fiber Optic Era (1988-Present):

TAT-8 (1988): First transatlantic fiber optic cable (280 Mbps)

Exponential capacity growth: Modern cables carry 200+ terabits per second

Current landscape: ~1.3 million kilometers of active submarine cables worldwide

1.2 Anatomy of a Modern Submarine Cable

Layered Construction:

Core: Hair-thin glass fibers (typically 4-8 pairs) Coating: Protective layers around each fiber Buffer: Gel-filled protection against water Strength Members: Steel wires for tensile strength Insulation: Copper sheathing for power transmission Protective Layers: Multiple polyethylene coatings Armor: Steel wires for shallow-water protection (not on deep-sea sections)

Typical Specifications:

Diameter: 17-50 mm (shallow water) vs. 17-25 mm (deep water)

Weight: 1-2 tons per kilometer (armored) vs. 0.5-1 ton/km (deep sea)

Repeater spacing: 50-150 km depending on cable design

Design life: 25 years (though many remain operational longer)

1.3 The Cable Laying Process

Survey Phase (6-12 months):

Bathymetric mapping of sea floor

Avoidance of geological hazards, shipwrecks, fishing zones

Negotiation of landing rights with coastal nations

Manufacturing Phase:

Continuous cable production in factories (up to 200km/day)

Repeater integration at specialized facilities

Testing of every kilometer before loading onto ships

Installation Phase:

Cable ships: Specialized vessels with dynamic positioning

Plowing: Buried 1-3 meters deep in shallow waters

Surface laying: Simply laid on ocean floor in deep waters

Branching units: Allow connections to multiple landing points

Post-Installation:

Burial documentation for future avoidance

Monitoring systems for fault detection

Maintenance agreements between cable consortium members

1.4 Global Cable Map and Strategic Chokepoints

Major Cable Systems:

FLAG Atlantic-1 (FA-1): 14,500 km, connecting US, UK, France

SEA-ME-WE 3/4/5: Southeast Asia-Middle East-Western Europe routes

Africa Coast to Europe (ACE): Connecting West Africa to Europe

Google’s Dunant: First 12-fiber pair cable (250 Tbps capacity)

Facebook’s 2Africa: Will become world’s largest cable system (37,000 km)

Strategic Chokepoints:

Strait of Malacca: 25+ cables concentrated in narrow passage

Suez Canal: Critical Mediterranean-Asia junction

Luzon Strait: Between Taiwan and Philippines

English Channel: Highest density of cables worldwide

Geopolitical Considerations:

China’s Digital Silk Road: Belt and Road Initiative includes submarine cables

US-China tensions: Battle for Pacific cable dominance

Island nations: Becoming cable hubs (Guam, Cyprus, Mauritius)

Arctic routes: Melting ice opening new northern passages

1.5 Vulnerabilities and Protection

Natural Threats:

Earthquakes: 2006 Hengchun earthquakes severed 9 cables

Sharks: Less common than myth suggests but documented

Fishing trawlers: Most common cause of cable damage (40-50% of faults)

Anchors: Particularly damaging in congested shipping lanes

Human Threats:

Intentional sabotage: Limited but increasing concern

Espionage: Tapping cables in territorial waters

Theft: Copper sheathing has been stolen in some regions

Protection Measures:

No-fishing zones: Around critical cable routes

Burial requirements: Up to 3 meters in shallow waters

Cable protection zones: Legal frameworks in many countries

Monitoring systems: Real-time surveillance of cable integrity

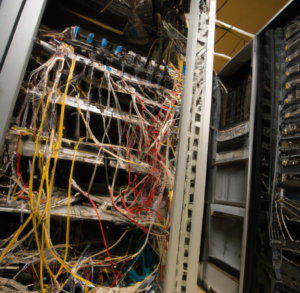

2. Data Centers: The Digital Heartlands

2.1 Evolution from Computer Rooms to Cloud Campuses

Mainframe Era (1960s-1980s):

Single-organization computer rooms

Raised floors, chillers, UPS systems

Limited connectivity to other facilities

Colocation Boom (1990s-2000s):

Carrier hotels and colocation facilities

Multi-tenant models emerge

Early internet companies require reliable hosting

Hyperscale Era (2010s-Present):

Facebook, Google, Amazon, Microsoft building mega-campuses

Facilities exceeding 1 million square feet

Specialization: Different designs for compute, storage, AI workloads

2.2 Anatomy of a Modern Hyperscale Data Center

Site Selection Criteria:

Geological stability: Low earthquake risk

Cooling potential: Access to water or cool air

Energy availability: Reliable, affordable power

Network connectivity: Proximity to fiber routes

Tax incentives: Often determining factor for locations

Power Infrastructure:

Typical consumption: 30-100+ megawatts per facility

Comparison: Equivalent to 30,000-100,000 homes

Redundancy: N+1 or 2N power systems

On-site generation: Often includes diesel generators

Grid integration: Some participate in demand response programs

Cooling Systems Evolution:

Computer Room Air Conditioning (CRAC): Traditional raised-floor cooling

Hot/Cold aisle containment: Separating intake/exhaust air

Free cooling: Using outside air when conditions permit

Liquid cooling: Direct-to-chip or immersion cooling for high-density racks

Ocean/river cooling: Facebook’s Sweden center uses Baltic Sea water

Compute Density Trends:

2000: 1-2 kW per rack

2010: 5-10 kW per rack

2020: 15-30 kW per rack (standard)

2024: AI clusters reaching 50-100+ kW per rack

2.3 The Global Data Center Geography

Major Concentration Zones:

Northern Virginia: “Data Center Alley” hosts 70% of global internet traffic

Silicon Valley: Declining relative share but still significant

Dublin, Ireland: European cloud hub benefiting from climate and taxes

Singapore: Southeast Asia’s primary hub despite space/power constraints

Beijing/Tianjin: China’s northern cluster

Emerging Frontiers:

Nordic countries: Iceland, Norway, Sweden with cheap renewable energy

Chile: Strategic position for Latin America-Southern Cone connectivity

Middle East: UAE and Saudi Arabia investing heavily

Africa: Johannesburg, Nairobi, Lagos emerging as regional hubs

The “Follow the Sun” Architecture:

Content delivery networks placing data near users globally

Trading firms locating servers milliseconds closer to exchanges

Cloud providers building regions based on customer concentration

2.4 Sustainability Challenges and Innovations

Energy Consumption Reality:

Global estimate: 1-2% of worldwide electricity (growing)

Projection: Could reach 4% by 2030 without efficiency improvements

Carbon emissions: Vary dramatically by energy grid

Innovations in Efficiency:

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) improvements:

2007 average: 2.5 (for every watt to IT, 1.5 to cooling/power)

2024 hyperscale: 1.1-1.3 (Google’s average: 1.10)

Renewable energy procurement: Google, Microsoft, Amazon are largest corporate buyers

Heat reuse: Warming community buildings in Nordic countries

Circular economy: Facebook’s data centers designed for disassembly

Water Usage Concerns:

Revelation: Microsoft’s Arizona data center to use 56 million gallons annually

Innovations: Air-cooled designs, closed-loop systems

Regulatory pressure: Increasing in water-stressed regions

2.5 Specialized Facilities

Content Delivery Network (CDN) Edge Nodes:

Thousands of small facilities globally

Typically 10-50 racks each

Located in internet exchanges or carrier hotels

Purpose: Cache content closer to end-users

Carrier Hotels and Colocation Hubs:

One Wilshire (Los Angeles): Pacific Rim interconnection hub

60 Hudson (New York): Historic telegraph building turned digital hub

Equinix DC1-15 (Ashburn, VA): Core of Data Center Alley

Telehouse (London): European interconnection center

Government and Financial Facilities:

NSA data centers: Utah Data Center (1 million sq ft, $1.5B cost)

Trading colocation: Sub-millisecond proximity to exchange servers

Disaster recovery sites: Geographically distant backup facilities

3. Internet Exchange Points (IXPs): The Network Meeting Points

3.1 What IXPs Do and Why They Matter

The Peering Principle:

Transit vs. Peering: Paying for connectivity vs. free exchange

Public peering: Multiple networks connect at shared fabric

Private peering: Direct connection between two networks

Settlement-free peering: No money changes hands

Key Benefits:

Reduced latency: Avoiding extra hops through transit providers

Cost reduction: Less paid transit required

Improved performance: More direct routing between networks

Resilience: Multiple interconnection options

3.2 Physical Infrastructure of IXPs

Switching Fabric Evolution:

Ethernet switches: Standard Layer 2 switching

Route servers: Simplify multilateral peering

Software-Defined Exchange (SDX): More flexible, programmable peering

Virtual cross-connects: Remote peering capabilities

Facility Requirements:

Carrier-neutral colocation space

Diverse fiber entry points

High-capacity power with redundancy

Physical security measures

24/7 technical support

Major Global IXPs:

DE-CIX Frankfurt: World’s largest by peak traffic (14+ Tbps)

AMS-IX Amsterdam: Historic European hub

LINX London: One of the world’s first IXPs

Equinix exchanges: Global platform of interconnected facilities

3.3 The Economics of Interconnection

Business Models:

Non-profit member associations (LINX, AMS-IX)

Commercial operators (Equinix, Digital Realty)

Hybrid models (DE-CIX combines both)

Pricing Structures:

Port-based: Charge per port speed (10G, 100G, 400G)

Volume-based: Charges based on traffic volume

Membership fees: Annual fees for participating networks

Cross-connect fees: Charging for physical connections within facility

The “Peering Ecosystem”:

Tier 1 networks: Don’t pay for transit (heavily peered)

Content providers: Major sources of traffic (Google, Netflix, Facebook)

Access networks: ISPs bringing end-user traffic

Cloud providers: Interconnecting with enterprise networks

3.4 Growth in Emerging Markets

African IXP Development:

Nairobi (KIXP): One of Africa’s largest and most successful

Johannesburg (JINX): Key Southern Africa hub

Lagos (IXPN): Growing West African exchange

Impact: Up to 90% reduction in local latency, 80% cost savings

Challenges in Developing Regions:

Regulatory barriers: Monopolies resisting interconnection

Limited technical expertise: Need for capacity building

Physical infrastructure: Reliable power and connectivity

Commercial models: Sustainable funding for operations

Success Stories:

Bangladesh: BDIX transformed local internet performance

Brazil: PTT Metro created vibrant ecosystem

Middle East: UAE-IX attracting regional networks

4. Interdependencies and Systemic Risks

4.1 Critical Infrastructure Interactions

Cable Landing Stations → Data Centers:

Typical flow: Cable lands → Carrier hotel → Backbone network → Data center

Location strategy: Data centers cluster near cable landing points

Ashburn example: Proximity to multiple transatlantic cables

Data Centers → IXPs:

Content providers: Place servers at IXPs for optimal peering

Cloud on-ramps: Direct connections from IXPs to cloud providers

The “flywheel effect”: More networks attract more content attracts more networks

IXPs → Network Backbones:

Backbone interconnection: Major networks meet at key IXPs

Regional distribution: IXPs distribute traffic to regional networks

The “tiered” internet: How traffic flows between access, regional, backbone networks

4.2 Systemic Vulnerabilities

Single Points of Failure:

Cable concentration: Too many cables through same choke points

Power dependence: Data centers reliant on specific power grids

Geographic clustering: Northern Virginia’s dominance creates systemic risk

Supplier concentration: Limited vendors for critical equipment

Cascading Failure Scenarios:

Cable cut → Traffic reroutes → Congestion at alternate paths

DDoS attack → Overwhelms IXP capacity → Affects all connected networks

Power outage → Data center fails → Services unavailable globally

Natural disaster → Multiple infrastructure elements affected simultaneously

Security Concerns:

Physical security: Protection against sabotage or theft

Supply chain security: Trust in equipment manufacturers

Cyber-physical attacks: Digital attacks affecting physical infrastructure

State-sponsored threats: Infrastructure as geopolitical target

4.3 Resilience and Redundancy Strategies

Geographic Diversity:

Multi-region deployment: Cloud providers across continents

Cable path diversity: Avoiding single points of failure

Disaster recovery sites: Hundreds of kilometers between primary and backup

Network Architecture:

Anycast routing: Multiple locations serving same IP addresses

Load balancing: Distributing traffic across multiple paths

Failover automation: Automatic rerouting around failures

Industry Initiatives:

Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security (MANRS): Improving routing security

Cable protection agreements: International cooperation on cable security

Data center resilience standards: Uptime Institute Tier standards

5. Future Trends and Developments

5.1 Technological Evolution

Submarine Cable Advances:

Space-division multiplexing: More fiber pairs per cable

Open cable systems: Disaggregating wet and dry components

Branching unit flexibility: Dynamic reconfiguration capabilities

Power feeding innovations: More efficient power transmission

Data Center Innovations:

AI-optimized designs: Different requirements for AI vs. traditional compute

Edge computing proliferation: Thousands of micro-data centers

Sustainable designs: Net-zero carbon, water-positive facilities

Automated operations: Robotics for maintenance and repairs

IXP Evolution:

Intercontinental IXPs: Remote peering across oceans

Virtual interconnection: Software-defined peering

Specialized exchanges: For IoT, financial, or research traffic

5.2 Geographic Shifts

Climate-Driven Relocation:

Heat waves affecting cooling efficiency in traditional locations

Water scarcity limiting certain regions

Renewable energy availability driving site selection

Potential winners: Nordic countries, Canada, Patagonia

Geopolitical Realignment:

US-China decoupling affecting cable routes

BRICS countries developing independent infrastructure

Arctic routes becoming viable with climate change

Africa developing intra-continental connectivity

Urban vs. Rural Balance:

Edge computing: Bringing infrastructure closer to users

Rural data centers: Utilizing cheaper land and energy

Urban micro-centers: Meeting low-latency requirements in cities

5.3 Policy and Regulation

Data Sovereignty Laws:

Requirements for data to remain within national borders

Impact on global cloud architecture

Emergence of “data embassies” for diplomatic data protection

Sustainability Regulations:

Carbon emission reporting requirements

Water usage limitations

Circular economy mandates for hardware

Security Standards:

Critical infrastructure protection laws

Supply chain security requirements

Resilience standards for cloud providers

Conclusion: The Tangible Foundations of Our Digital World

The internet’s physical infrastructure represents one of humanity’s most remarkable engineering achievements—a globally distributed, real-time nervous system that has fundamentally transformed civilization. From the ocean floors crisscrossed by fiber-optic cables to the vast data centers humming with computation to the unassuming buildings where networks exchange traffic, this physical layer remains largely invisible to end users yet forms the essential foundation of digital life.

Three key realities emerge from examining this infrastructure:

The internet is profoundly physical: Every byte travels through copper, glass, or air, consuming real energy and requiring physical maintenance.

It is inherently global yet locally concentrated: While spanning the planet, critical infrastructure clusters in specific regions due to economic, geographic, and historical factors.

It is both resilient and fragile: Designed with redundancy yet vulnerable to concentrated attacks, natural disasters, and systemic risks.

As we look to the future, several challenges loom:

Sustainability: Balancing growing demand with environmental constraints

Equity: Ensuring global access not determined by infrastructure geography

Security: Protecting critical infrastructure in an increasingly contested world

Governance: Developing frameworks for global infrastructure with local impacts

The evolution of this infrastructure will shape the internet’s next chapter. Will it become more centralized in massive hyperscale facilities or distributed through edge computing? Will it follow clean energy sources or maintain traditional locations? Will it reinforce existing digital divides or help bridge them?

Ultimately, understanding the internet’s physical backbone reminds us that digital transformation rests on material foundations. As we build the metaverse, expand artificial intelligence, and connect billions more devices, we must remember that all these virtual capabilities depend on very real cables, servers, and exchange points—the unsung heroes of our connected age.

Key Statistics and Data Points

Submarine cables: Carry ~99% of international data traffic

Total cable length: Enough to wrap around Earth 30+ times

Data center electricity: Could power all UK homes twice over

IXP traffic growth: 45% CAGR in emerging markets

Cost of cable cut: Estimated $100,000-$1,000,000 per hour for financial sector

Further Resources

Submarine Cable Map: https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Data Center Map: https://www.datacentermap.com/

PeeringDB: Database of networks and interconnection data

Telegeography: Research on global internet infrastructure

The internet may live in the cloud, but it’s built on steel, glass, and silicon—a testament to human ingenuity in creating connections that transcend geography while remaining firmly grounded in physical reality.