Modular Phone Progress

The Modular Phone Dream: A History of Ambition, Failure, and Lasting Influence

The vision was seductive and revolutionary: a smartphone you could upgrade like a desktop PC. A cracked screen swapped in seconds. A fading battery replaced over lunch. A better camera attached without buying a whole new device. This was the promise of modular phones—a concept that flared brightly in the tech imagination before seemingly vanishing. But its story is not one of simple failure; it’s a complex tale of ambitious engineering, harsh market realities, and a legacy that permanently reshaped the industry’s conversation around repairability and sustainability.

The Grand Vision: Phone as Ecosystem, Not Monolith

At its core, the modular phone proposed a fundamental redesign. Instead of a sealed, integrated slab, it would be a core “frame” or “endo-skeleton” with slots or connectors for hot-swappable components, or “modules.” These could include:

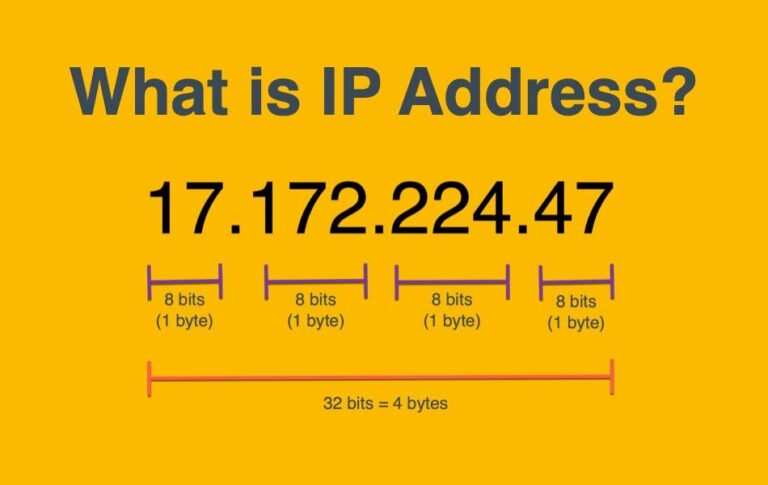

Core Performance: CPU, RAM, and storage.

Essential Peripherals: Cameras, speakers, batteries.

Specialized Functions: Advanced thermal imagers, physical keyboards, enhanced audio DACs, rugged casings, or medical sensors.

The theoretical benefits were immense: dramatically reduced electronic waste, long-term cost savings for consumers, hyper-customization, and a potential third-party hardware ecosystem akin to the app store.

The Flagship Failure: Google’s Project Ara

The apex of modular ambition was Google’s Project Ara, announced in 2013. Its vision was the most radical: an open hardware platform where the entire phone—aside of a small core frame—could be built from swappable, magnetically-attached modules. You could, in theory, pop out a generic camera module and click in a professional-grade one from Zeiss, or add a larger battery for a weekend trip.

Why It Failed Spectacularly:

Technical Nightmares: Magnets and connectors couldn’t match the reliability of soldered circuits. Modules would work loose, connections corrode, and data transfer speeds lag behind integrated designs. The result was a device inherently thicker, heavier, and less robust than its monolithic competitors.

Economic Unviability: Creating a single, popular smartphone model is astronomically expensive. Project Ara asked manufacturers to develop and stock dozens of small, interoperable modules for an unproven market—a logistical and financial quagmire. Who would invest millions to build the best “E-Ink display module” for a niche platform?

The Paradox of Choice: While enticing to tech enthusiasts, mainstream consumers overwhelming prefer simplicity. The burden of researching, sourcing, and maintaining a box of modules proved to be a feature, not a bug, for the general public.

Google shelved Ara in 2016, a symbolic death knell for the “Lego phone” dream.

The Pragmatic Survivor: Fairphone’s Modular Ethos

If Project Ara was the idealistic revolution, Fairphone has been the pragmatic evolution. The Dutch social enterprise’s approach is not about performance customization, but ethical repairability. Their latest model, the Fairphone 5, is a masterclass in this philosophy.

The Fairphone Modular Difference:

Modular for Repair, Not Upgrade: You cannot upgrade its SoC (System on a Chip). However, you can, with a common screwdriver, replace the screen, battery, camera modules, USB port, speaker, and even the rear case in under 10 minutes each. Parts are readily available and reasonably priced.

Sustainable by Design: Every component is sourced with conflict-free minerals and fair labor practices as a priority. The design guarantees long-term software support (promised until 2031) and easy hardware repair.

Market Reality: Fairphone proves modularity is technically possible, but it succeeds by limiting its scope. It targets a specific, values-driven consumer segment, not the mass market. It is thicker and mid-tier in performance, trading sleekness for sustainability—a trade its customers willingly accept.

Why the Mainstream Dream Died: The Inescapable Trade-offs

The failure of mainstream modularity stems from fundamental conflicts with industry and consumer forces:

The Tyranny of Thinness: The smartphone market ruthlessly prioritizes sleek, waterproof, rigid designs. Modular connectors, extra casing, and replaceable parts add millimeters and complexity that consumers, trained by Apple and Samsung, largely reject.

Performance Integration: Modern smartphone performance is a ballet of tightly integrated hardware. A system-on-a-chip (SoC) is engineered in tandem with specific RAM, storage, and sensors. Swappable components create bottlenecks, throttling the very performance high-end buyers seek.

The Planned Obsolescence Economy: The tech industry’s profit engine is built on regular, full-device upgrade cycles. A truly upgradeable phone disrupts this core business model. It’s more profitable to sell you a new $1,000 phone every three years than a $200 camera module.

Supply Chain Simplicity: Managing global logistics for a handful of phone models is complex enough. A modular system with dozens of SKUs for parts, warranties, and regional compatibility is a manufacturer’s nightmare.

The Lasting Legacy: How Modularity Changed the Game

While the modular phone as envisioned didn’t conquer the world, its DNA is everywhere:

The Right-to-Repair Movement: Fairphone is its poster child. Modularity’s ethos directly fueled the global push for legislation mandating repairable designs, accessible parts, and repair manuals. The Framework Laptop is a direct spiritual successor in the PC space.

Mainstream Concessions: Even Apple and Samsung now offer official battery and screen replacements, publish repair manuals (under pressure), and design newer devices with slightly more repairable internals. This is a direct response to the demand modularity highlighted.

Specialized & Rugged Devices: The modular concept lives on in industrial, military, and enterprise settings. Devices from companies like Bullitt Group (makers of CAT phones) often feature modular add-ons like barcode scanners or extended battery packs for fieldwork.

The Future: Niche Evolution, Not Mass Revolution

The future of modular phones is not a return to Project Ara. Instead, it lies in three directions:

The Fairphone Path: Continued refinement of ethically repairable, long-life devices for the conscious consumer. Success is measured in environmental impact, not market share.

Accessory-Led “Modularity”: Using standardized, external ports (like USB-C) for functional add-ons. Think of powerful external microphone adapters, gaming cooler fans, or projector attachments. This offers customization without compromising the core device’s integrity.

Regulatory Forced Evolution: Strong right-to-repair laws, like those emerging in the EU and parts of the US, may force all manufacturers to adopt Fairphone-like modularity for key components (batteries, screens). This would make modularity a standard, not a niche feature.

Conclusion: A Beautiful, Impractical Dream That Left a Mark

The dream of a fully modular, upgradeable smartphone was a beautiful answer to a problem—electronic waste and consumer powerlessness—that the market was not truly ready to solve. It crashed against the rocks of physics, economics, and human desire for simple, elegant objects.

Yet, its legacy is undeniable. The modular phone experiment was a necessary provocation. It proved that another way was technically possible and, in doing so, shamed the industry for its wasteful practices. It empowered a generation of tinkerers and activists who are now winning the fight for the right to repair. We may never have our Lego phones, but because of that dream, our next phone will be a little easier to fix, a little longer-lasting, and a little more our own. The modular revolution didn’t fail; it simply evolved into a slower, more profound change in the very fabric of consumer technology.

OTHER POSTS