The Basics of Encryption: How Your Data Stays Safe Online.

The Basics of Encryption: How Your Data Stays Safe Online

The Invisible Shield

Every time you check your bank balance, send a private message, or type a password into a website, an invisible shield snaps into place. Without it, your most sensitive information would be broadcast in plain view—readable by your internet service provider, anyone sharing your Wi-Fi, and every router between you and your destination. That shield is encryption, and it is the single most important technology protecting your digital life.

Yet encryption remains mysterious to most people. It’s often portrayed as unbreakable mathematical magic, accessible only to codebreakers and spies. The reality is far more elegant. Encryption is not magic; it’s a logical system of locks and keys that anyone can understand. This guide will demystify that system, explaining exactly how your data stays safe and why, despite its power, encryption is not a complete solution on its own.

Part 1: The Core Problem—Communicating Secrets in Public

Imagine you need to send a secret message to a friend, but you know that anyone could intercept it. You have two options:

Share a secret code beforehand that both of you use to scramble and unscramble messages.

Devise a way for your friend to send you a lock that only they can unlock, without ever meeting.

These two approaches are the foundation of all modern encryption. They are called symmetric encryption and asymmetric encryption, and every secure transaction you make online uses both.

The vocabulary you need:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Plaintext | The original, readable message or data. |

| Ciphertext | The scrambled, unreadable output of encryption. |

| Encryption | The process of converting plaintext to ciphertext. |

| Decryption | The reverse process, restoring plaintext from ciphertext. |

| Key | A secret value (usually a string of numbers) used to control encryption and decryption. |

| Algorithm | The mathematical procedure (cipher) that performs encryption and decryption. |

Part 2: Symmetric Encryption—The Shared Secret

How it works:

Symmetric encryption uses the same key to encrypt and decrypt. You and your recipient must both possess this identical key, and it must remain secret from everyone else.

The analogy: You put your message in a box, lock it with a padlock, and send the box. Your friend has an identical key to that same padlock. They unlock it and read the message.

Real-world examples:

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard): The current global standard, used by the U.S. government for classified information. AES-256 uses a 256-bit key—there are more possible keys than atoms in the observable universe.

ChaCha20: A modern stream cipher, particularly efficient on mobile devices, used in Google’s HTTPS connections and WhatsApp.

Strengths:

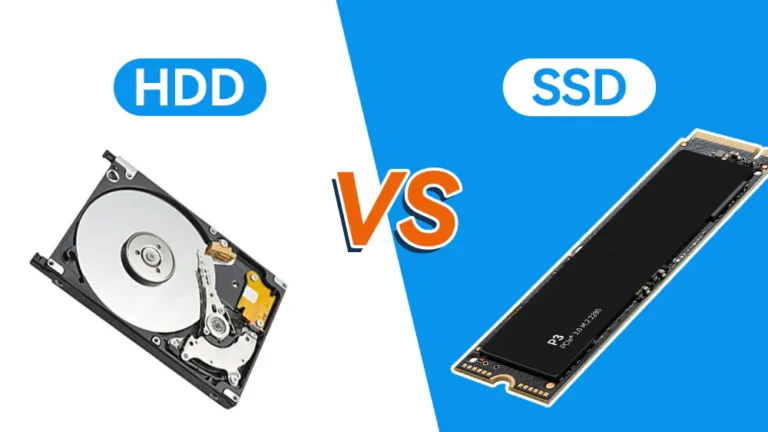

Extremely fast. Symmetric encryption is computationally lightweight and can encrypt gigabytes of data in seconds.

Very secure when implemented correctly with strong keys.

The fatal weakness:

Key distribution. How do you securely share the secret key with your recipient? If you send it over the same channel you’re trying to protect, an eavesdropper can intercept it. If you meet in person, that’s impractical for global communication. This problem—the key exchange problem—was the central barrier to secure communication for centuries.

Part 3: Asymmetric Encryption—The Genius Solution

How it works:

Asymmetric encryption (also called public-key cryptography) solves the key distribution problem with a brilliant twist: instead of one key, you have two mathematically linked keys—a public key and a private key.

The public key can be shared with anyone. It is used to encrypt messages.

The private key is kept absolutely secret. It is used to decrypt messages encrypted with its corresponding public key.

The analogy: You send your friend an open padlock (the public key). They put their message in a box, snap your lock shut, and send it. Even they cannot reopen the lock. Only you, with your private key, can open it.

The mathematics (simplified):

Most asymmetric algorithms (like RSA) are based on trapdoor functions—mathematical operations that are easy to perform in one direction but extraordinarily difficult to reverse without secret knowledge.

Multiplication is easy; factoring the product of two enormous prime numbers is computationally infeasible. RSA exploits this asymmetry. Your public key includes the product of two primes; your private key includes the primes themselves. Anyone can encrypt using the product, but only you know the factors needed to decrypt.

Real-world algorithms:

RSA: The classic, based on integer factorization. Key lengths of 2048 or 4096 bits are standard.

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): Achieves equivalent security with much shorter keys, making it ideal for mobile devices and modern TLS.

Strengths:

Solves key distribution. Public keys can be shared openly; private keys never leave your device.

Enables digital signatures (see Part 5).

Weakness:

Extremely slow. Asymmetric encryption is hundreds to thousands of times slower than symmetric encryption. Encrypting a large file directly with RSA would be impractical.

Part 4: Hybrid Encryption—The Best of Both Worlds

How it works:

Real-world encryption doesn’t choose between symmetric and asymmetric; it uses both in a hybrid system.

Asymmetric encryption is used to securely exchange a temporary, random symmetric key. This is called the session key.

All subsequent data is encrypted with fast symmetric encryption using that session key.

At the end of the session, the session key is discarded.

This is exactly how HTTPS (SSL/TLS) works.

The TLS handshake (simplified):

Hello: Your browser connects to a website and requests a secure connection.

Certificate: The server presents its digital certificate, which contains its public key and proof of identity.

Key exchange: Your browser generates a random session key, encrypts it with the server’s public key, and sends it.

Symmetric encryption: Both parties now have the same session key. All subsequent traffic (the webpage, your form submissions) is encrypted with AES or ChaCha20.

End: The session key is discarded. A new one is generated for your next visit.

This hybrid model gives you the security of asymmetric key exchange with the speed of symmetric encryption.

Part 5: Hashing—The One-Way Street

Encryption is reversible (with the key). Sometimes you don’t need reversibility; you need integrity verification.

What is a hash?

A cryptographic hash function takes an input (any size) and produces a fixed-size output—a digest or hash. Crucially, it is one-way: you cannot reverse the hash to discover the original input.

Properties of a secure hash:

Deterministic: Same input always produces same hash.

Fast to compute.

Preimage resistant: Given a hash, infeasible to find an input that produces it.

Collision resistant: Infeasible to find two different inputs with the same hash.

Real-world algorithms:

SHA-256 (Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit): Currently the standard; used in Bitcoin, TLS certificates, and software verification.

SHA-3: The newest NIST standard, designed as a backup in case SHA-2 is broken.

Common uses of hashing:

Password storage. Smart services don’t store your password; they store its hash. When you log in, they hash what you type and compare hashes. If their database is stolen, attackers get only hashes, not passwords.

File integrity. When you download software, the provider often publishes a SHA-256 hash. You compute the hash of your downloaded file; if it matches, the file hasn’t been tampered with.

Digital signatures. A hash of a message is signed with a private key, proving both authenticity and integrity.

Part 6: Digital Signatures—Proving You Are Who You Say You Are

Encryption provides confidentiality. Digital signatures provide authenticity and non-repudiation.

How they work:

Alice creates a message and computes its hash.

Alice encrypts the hash with her private key. This encrypted hash is her signature.

Alice sends the message and signature.

Bob decrypts the signature using Alice’s public key, recovering the hash.

Bob computes the hash of the received message. If it matches the decrypted hash, the message is authentic and unaltered.

What a signature proves:

Authenticity: Only Alice’s private key could have produced this signature.

Integrity: The message has not been changed since signing.

Non-repudiation: Alice cannot later deny signing it (unless her private key was compromised).

Real-world applications:

Code signing (proving software comes from a legitimate developer)

Document signing (PDF signatures, DocuSign)

Email signing (S/MIME, PGP)

Blockchain transactions

Part 7: Certificates and PKI—The Web of Trust

You’ve connected to your bank’s website. Your browser has received its public key. How do you know this public key actually belongs to your bank, not an attacker?

The answer: Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) and digital certificates.

What is a certificate?

A digital certificate is an electronic document that binds a public key to an identity (person, organization, device). It contains:

The subject’s name (e.g., “bankofamerica.com“)

The subject’s public key

The issuer’s name (a Certificate Authority)

A digital signature from the issuer

Validity dates

Serial number

Certificate Authorities (CAs):

CAs are trusted third-party organizations (DigiCert, Let’s Encrypt, GlobalSign) that verify identities and issue certificates. Your operating system and browser come pre-loaded with a list of root certificates from trusted CAs.

The chain of trust:

Your browser trusts the root CAs (they’re built-in).

A root CA signs a certificate for an intermediate CA.

The intermediate CA signs your bank’s certificate.

Your browser follows this chain back to a trusted root. If every signature is valid, the bank’s certificate is trusted.

Why this matters:

Without PKI, you could never be sure you’re communicating with the real website. An attacker could intercept your connection, present their own public key, and claim to be your bank. With PKI and properly validated certificates, that attack (a man-in-the-middle attack) is detected because the attacker’s certificate won’t be signed by a trusted CA for your bank’s domain.

Part 8: Encryption in Everyday Life—Where You’re Already Using It

HTTPS (The Padlock Icon)

Every modern website should use HTTPS. It provides:

Encryption: Your traffic is unreadable to eavesdroppers.

Authentication: You’re connected to the genuine website, not an impostor.

Integrity: Data cannot be modified in transit without detection.

End-to-End Encrypted Messaging

WhatsApp, Signal, and iMessage use end-to-end encryption (E2EE). Messages are encrypted on your device and only decrypted on the recipient’s device. The service provider cannot read them. This is typically implemented with the Signal Protocol, a sophisticated hybrid of asymmetric and symmetric encryption with forward secrecy (if a key is compromised, past messages remain secure).

Email Encryption

TLS in transit: Most email providers encrypt connections between mail servers using TLS. This protects against eavesdropping between servers, but the email provider itself can read your mail.

End-to-end email encryption: PGP/GPG or S/MIME encrypts the message body so that only the intended recipient can decrypt it. This is more secure but significantly harder to use.

VPNs

A VPN encrypts all traffic between your device and the VPN server. Your ISP sees only that you’re connected to a VPN; your browsing, DNS queries, and application data are encrypted inside the tunnel.

Wi-Fi Encryption

WPA2/WPA3: Encrypts all traffic between your device and the wireless access point, protecting you from other users on the same network.

Unencrypted Wi-Fi (open networks): No encryption; any traffic not using HTTPS is visible to anyone nearby.

Full Disk Encryption

Tools like BitLocker (Windows), FileVault (macOS), and LUKS (Linux) encrypt your entire hard drive. If your laptop is stolen, the thief cannot read your files without the decryption key (your password).

Part 9: The Limits of Encryption—What It Cannot Do

Encryption is powerful, but it is not a complete security solution.

Encryption does not protect against:

Phishing. You can have perfect TLS encryption and still hand your credentials to a fake website that looks legitimate.

Malware on your device. If your computer is infected with a keylogger, encryption is irrelevant—the attacker reads your keystrokes before they’re encrypted.

Weak passwords. Encryption is only as strong as the keys protecting it. A weak password can be brute-forced.

Metadata. Encryption typically hides the content of your communication, but not necessarily who you’re communicating with, when, or how much data you’re sending. This metadata can be highly revealing.

Compelled disclosure. In many jurisdictions, courts can order you to decrypt your devices or provide keys.

The human element remains the weakest link. No amount of mathematical security can compensate for poor operational security, social engineering, or insider threats.

Conclusion: The Mathematics of Trust

Encryption is a triumph of applied mathematics. It transforms the abstract properties of prime numbers, elliptic curves, and hash functions into practical tools that protect billions of daily transactions. It enables commerce, private communication, and the preservation of confidential information in an age of ubiquitous surveillance.

Yet encryption is not a passive shield. It requires active, correct implementation. It depends on the integrity of certificate authorities, the strength of random number generators, and the diligence of software developers. Most of all, it depends on you—recognizing the padlock icon, verifying certificate warnings, and understanding that the lock on your browser is not a guarantee of safety, but a tool that must be used correctly.

The next time you see that small padlock in your address bar, you are witnessing the result of decades of cryptographic research, international standardization, and global infrastructure. It is, quite literally, the lock on the digital world. And now you understand exactly how it works.

OTHER POSTS