Cloud Computing Explained: IaaS, PaaS, SaaS.

Cloud Computing Demystified: IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS Explained

From Server Rooms to Invisible Infrastructure

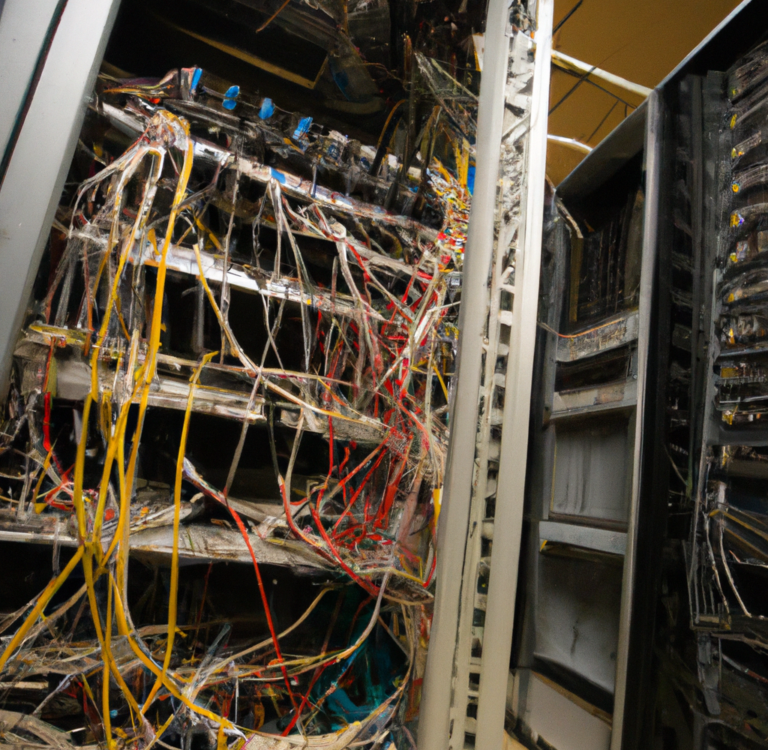

Not long ago, launching a software product meant a capital-intensive ritual: you estimated peak traffic, purchased physical servers, reserved rack space in a data center, installed networking equipment, configured cooling and power redundancy, and hired staff to maintain it all. This process took months. If you underestimated demand, your service crashed. If you overestimated, you wasted millions on idle equipment.

Cloud computing eliminated this entire paradigm.

Today, you can provision computing resources in seconds, pay only for what you use, and scale from a single user to millions without ever touching a physical server. This transformation is not just about technology—it is a fundamental shift in how businesses operate, how software is built, and how value is delivered.

Yet despite its ubiquity, cloud computing remains poorly understood. The terms IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS are frequently used but rarely explained with clarity. They are not marketing buzzwords; they represent distinct service models with profound implications for control, responsibility, and cost. This guide will demystify each layer, provide concrete examples, and equip you to make informed decisions about which model fits your needs.

Part 1: The Core Idea—Computing as a Utility

The fundamental insight of cloud computing: Infrastructure, platforms, and software are no longer assets you purchase and own. They are services you consume, like electricity or water.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines cloud computing by five essential characteristics:

| Characteristic | What It Means |

|---|---|

| On-demand self-service | Users can provision resources automatically without human interaction with the provider. |

| Broad network access | Services are available over the network via standard mechanisms (not physical media). |

| Resource pooling | Provider resources are pooled to serve multiple consumers, dynamically assigned and reassigned. |

| Rapid elasticity | Capabilities can be elastically provisioned and released, often automatically, to scale rapidly. |

| Measured service | Usage is monitored, controlled, and reported. You pay for what you consume. |

The Abstraction Ladder:

The three cloud service models—IaaS, PaaS, SaaS—represent different rungs on an abstraction ladder. As you climb:

You lose control over the underlying infrastructure.

You gain efficiency and reduced operational burden.

Your responsibility shifts from managing technology to using technology.

Understanding this trade-off is the key to choosing the right model.

Part 2: IaaS—Infrastructure as a Service

The definition: IaaS provides on-demand access to IT infrastructure—servers, virtual machines, storage, networks, and operating systems. You do not manage the physical hardware; you control the operating system, middleware, runtime, data, and applications.

The analogy: Renting a fully constructed, empty warehouse. You have the keys, you control the layout, you install your equipment, you secure the doors. The landlord ensures the roof doesn’t leak and the power grid functions.

What you manage vs. what the provider manages:

| Your Responsibility | Provider’s Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Operating system updates and patching | Physical data centers |

| Installed applications and middleware | Network cabling and switches |

| Data security and access controls | Server hardware maintenance |

| Virtual network configuration | Power, cooling, physical security |

Real-world examples:

Amazon Web Services (AWS) EC2: Virtual servers in the cloud. You choose the operating system, CPU, memory, storage, and network configuration.

Microsoft Azure Virtual Machines: Similar to EC2, integrated with Microsoft’s ecosystem.

Google Compute Engine: Google’s virtual machine offering.

DigitalOcean Droplets: Simplified IaaS focused on developer experience.

Ideal use cases:

Lift-and-shift migrations: Moving on-premises workloads to the cloud with minimal modification.

Applications requiring specific OS configurations: Legacy software that demands particular kernel versions or system libraries.

Custom networking architectures: Complex virtual private cloud (VPC) configurations, network appliances, or hybrid cloud setups.

Short-term, burst-capacity needs: Rendering farms, scientific computing, or batch processing jobs.

Advantages:

Complete control. You are not constrained by a platform’s limitations.

Familiarity. If you know how to administer a physical server, you know how to administer a virtual server.

Portability. IaaS images can often be moved between providers with less friction than PaaS applications.

Disadvantages:

Operational burden. You are responsible for patching, securing, and maintaining the OS and middleware.

Underutilization risk. Without careful management, you can pay for idle resources.

Complexity. Designing for high availability, disaster recovery, and auto-scaling requires significant expertise.

Part 3: PaaS—Platform as a Service

The definition: PaaS delivers a complete development and deployment environment in the cloud. You do not manage the underlying infrastructure (servers, operating systems, storage) or the runtime environment. You focus exclusively on writing and deploying code.

The analogy: Renting a fully equipped commercial kitchen. You don’t install the ovens, repair the plumbing, or inspect the gas lines. You bring your ingredients and recipes, cook your meals, and serve customers. The kitchen owner ensures the equipment works, the health code is met, and the dishwasher runs.

What you manage vs. what the provider manages:

| Your Responsibility | Provider’s Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Application code | Physical data centers |

| Data and access controls | Server hardware and OS |

| Application configuration | Runtime environment (Node.js, Python, Java, etc.) |

| Middleware (web servers, databases) | |

| Scaling, load balancing, availability |

Real-world examples:

Heroku: The pioneer of developer-friendly PaaS. Deploy applications with

git push.Google App Engine: Automatically scales applications written in supported languages.

AWS Elastic Beanstalk: Abstracts EC2, auto-scaling, and load balancing into a simplified deployment interface.

Azure App Service: Hosts web applications, REST APIs, and mobile backends.

Firebase: Google’s mobile and web application platform, emphasizing real-time databases and authentication.

Ideal use cases:

Web applications and APIs. The vast majority of modern web apps do not require custom server configuration.

Prototyping and MVPs. Speed of deployment is critical; operational concerns are secondary.

Teams without dedicated operations staff. Startups, internal tools, and lines of business.

Event-driven and serverless architectures. Functions as a Service (FaaS) is an extreme form of PaaS.

Advantages:

Dramatically reduced operational overhead. No patching, no OS updates, no middleware configuration.

Built-in scalability. Most PaaS offerings include auto-scaling with minimal configuration.

Focus on business logic. Developers write code that delivers value, not infrastructure boilerplate.

Predictable costs. Pay for application instances and resources consumed.

Disadvantages:

Vendor lock-in. PaaS abstractions vary significantly between providers. Migrating a Heroku application to Azure App Service is not trivial.

Reduced control. You cannot install custom system libraries or modify the runtime environment beyond provider-specified limits.

Debugging complexity. When something goes wrong deep in the platform stack, you have limited visibility.

Cost at scale. For very large, predictable workloads, IaaS can be more cost-effective than PaaS.

The Serverless Evolution:

Functions as a Service (FaaS)—AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions—takes PaaS to its logical extreme. You upload individual functions, and the provider executes them in response to events, scaling from zero to infinity with no idle capacity. You pay only for execution time. This is the ultimate abstraction, but it imposes severe constraints on execution duration, state management, and runtime environment.

Part 4: SaaS—Software as a Service

The definition: SaaS delivers complete, ready-to-use applications over the internet. You do not manage infrastructure, platforms, or even the application itself. You simply use the software.

The analogy: Dining at a restaurant. You do not build the kitchen, install the appliances, write the recipes, or cook the food. You choose from the menu, place your order, and eat. The restaurant handles everything else.

What you manage vs. what the provider manages:

| Your Responsibility | Provider’s Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Your data | Physical infrastructure |

| User access and permissions | Operating systems and runtime |

| Configuration within application limits | Application code and updates |

| Data storage and backups | |

| Security patches and compliance | |

| Scaling and availability |

Real-world examples:

Google Workspace (Gmail, Google Docs, Google Drive): Complete productivity suite.

Microsoft 365: Word, Excel, Outlook, Teams delivered as services.

Salesforce: Customer relationship management (CRM).

Slack: Team communication.

Dropbox: File storage and synchronization.

Zoom: Video conferencing.

Ideal use cases:

Business productivity. Email, document creation, collaboration tools.

Customer relationship management. Sales pipelines, contact management, marketing automation.

Human resources and finance. Payroll, expense reporting, applicant tracking.

Any standardized business function. If the software meets your needs without customization, SaaS is optimal.

Advantages:

Zero infrastructure management. No servers, no platforms, no application maintenance.

Immediate availability. Sign up and start using in minutes.

Automatic updates. Providers continuously improve software and fix security vulnerabilities.

Global accessibility. Access from any device with an internet connection.

Predictable subscription pricing. Operational expense, not capital expense.

Disadvantages:

Limited customization. You cannot modify core functionality; you configure within predefined parameters.

Data residency and sovereignty concerns. Your data resides on the provider’s infrastructure, potentially across borders.

Integration challenges. Connecting SaaS applications to each other and to internal systems requires middleware (iPaaS) or custom development.

Vendor lock-in. Exporting years of accumulated data from a SaaS platform can be technically and financially difficult.

Shared responsibility confusion. While the provider secures the application, you remain responsible for user access controls, data classification, and compliance.

Part 5: The Shared Responsibility Model

One of the most critical—and most misunderstood—aspects of cloud computing is the shared responsibility model. Security and compliance are not simply “the cloud provider’s problem.” They are divided between provider and customer, and the division shifts depending on the service model.

| Service Model | Provider Responsible For | Customer Responsible For |

|---|---|---|

| IaaS | Physical security, hardware, virtualization, network infrastructure. | OS patches, application security, network ACLs, data encryption, identity management. |

| PaaS | Physical, hardware, OS, runtime, middleware, scaling. | Application code, data, access controls, configuration. |

| SaaS | Everything except customer data and user access. | Data classification, user permissions, client devices, compliance configuration. |

The critical insight: There is no service model where the customer has zero responsibility. Even in SaaS, you are responsible for:

Who has access to your data.

How your users authenticate.

Compliance with industry regulations (HIPAA, GDPR, etc.) as they apply to your use of the service.

Backing up your data if the provider’s retention policies are insufficient.

Part 6: Choosing the Right Model—A Decision Framework

There is no universally “best” cloud service model. The optimal choice depends on your resources, requirements, and constraints.

Choose IaaS when:

You are migrating existing applications with minimal modification.

You have specialized infrastructure requirements (specific OS versions, custom networking, legacy dependencies).

You have a skilled operations team that can manage servers effectively.

You need portability across cloud providers or hybrid environments.

You are optimizing for cost at very large, predictable scale.

Choose PaaS when:

You are building new cloud-native applications.

Your team prioritizes development velocity over infrastructure control.

You want to eliminate OS and middleware patching responsibilities.

Your application can run within the constraints of the platform.

You are willing to accept some vendor lock-in for operational simplicity.

Choose SaaS when:

A commercial off-the-shelf solution meets your business requirements.

You want to outsource the entire operational burden.

You need immediate deployment with minimal upfront investment.

The function is not a competitive differentiator (email, CRM, productivity tools).

Your organization lacks the expertise to build or maintain the equivalent capability.

Part 7: Beyond the Trinity—Emerging Service Models

The IaaS-PaaS-SaaS taxonomy, while foundational, no longer captures the full complexity of the cloud ecosystem. Several specialized models have emerged:

FaaS (Functions as a Service): As discussed, an extreme form of PaaS. AWS Lambda, Cloudflare Workers.

CaaS (Containers as a Service): Orchestration platforms (Kubernetes) delivered as a managed service. AWS EKS, Azure AKS, Google GKE. Sits between IaaS and PaaS.

iPaaS (Integration Platform as a Service): Cloud-based integration middleware. Connects SaaS applications, on-premises systems, and other cloud services. Workato, MuleSoft, Dell Boomi.

DBaaS (Database as a Service): Managed database platforms. AWS RDS, MongoDB Atlas, Snowflake.

DaaS (Desktop as a Service): Virtual desktops delivered from the cloud. AWS WorkSpaces, Azure Virtual Desktop.

BPaaS (Business Process as a Service): Entire business processes outsourced to a provider. Payroll processing, claims administration.

Part 8: The Economics of Cloud—CapEx vs. OpEx

Before cloud computing, IT infrastructure was capital expenditure (CapEx) . You purchased servers, software licenses, and data center space—upfront costs that depreciated over years.

Cloud computing shifts spending to operational expenditure (OpEx) . You pay recurring subscription or consumption-based fees.

This shift has profound implications:

| Traditional (On-Premises) | Cloud (IaaS/PaaS/SaaS) |

|---|---|

| Large upfront investment | Minimal upfront cost |

| Multi-year depreciation cycles | Monthly or pay-as-you-go billing |

| Fixed capacity, planned for peak | Elastic capacity, matches demand |

| Slow to scale, requires procurement | Instantaneous scaling |

| Idle resources cost you money | Idle resources can be terminated |

The economic trap: Cloud’s low barrier to entry and granular billing can mask runaway costs. Without rigorous governance, organizations accumulate thousands of underutilized resources and SaaS subscriptions. FinOps—the discipline of cloud financial management—has emerged in response.

Part 9: The Future—Abstraction Continues

The trajectory of cloud computing is clear: continuous abstraction upward.

IaaS abstracted physical hardware. PaaS abstracted operating systems and middleware. Serverless abstracted application instances. The next frontiers are:

Zero-infrastructure: AI-assisted development where applications are described, not coded, and the platform generates, deploys, and operates them.

Distributed cloud: Cloud services extended to edge locations and even on-premises environments, managed centrally from the provider’s control plane.

Industry clouds: Pre-packaged combinations of IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS tailored for specific regulated industries (healthcare, financial services, government).

Conclusion: Climbing the Abstraction Ladder

Cloud computing is not a single technology but a spectrum of service models, each representing a different point on the trade-off curve between control and convenience.

IaaS gives you the keys to the infrastructure. You drive, you maintain, you repair.

PaaS gives you a fully tuned engine. You steer, but the mechanics are invisible.

SaaS gives you transportation as a service. You choose the destination and depart.

There is no shame in choosing any rung of this ladder. The organization that builds its core competitive advantage on custom IaaS configurations is not more “real” than the startup that builds its MVP entirely on PaaS, or the enterprise that runs its HR on SaaS. They have simply made different trade-offs.

The question is not “Which model is best?” but “Which model is best for this specific workload, given our team, our constraints, and our objectives?”

Answer that question honestly, workload by workload, and you have mastered cloud computing.

OTHER POSTS