Demystifying Version Control: A Beginner’s Guide to Git.

Demystifying Version Control: A Beginner’s Guide to Git

The Nightmare Before Version Control

Picture this: You’re working on an important document—a novel, a research paper, or perhaps the final report for a client. You’ve made significant changes, but something feels wrong. The new direction isn’t working. You need to go back to yesterday’s version. But you saved over it. Your only “backup” is a file named final_report_v3_actually_final_REAL_FINAL.docx, and you’re not even sure what’s in it anymore.

This chaos is the default state of digital creation. Now imagine a world where every meaningful change is tracked, where you can instantly revert to any previous state, where multiple people can work on the same files simultaneously without accidentally destroying each other’s work, and where every change has an attached explanation of why it was made. This is the world of version control, and Git is its undisputed king.

This guide will not just teach you Git commands—it will transform how you think about creating and collaborating on digital projects.

Part 1: The Mental Model—What Git Actually Is

Most Git tutorials immediately drown you in commands: commit, push, pull, merge, rebase. This is pedagogically backward. Before you type a single command, you must understand what Git is at a conceptual level.

Git is a time machine for text.

More precisely, Git is a directed acyclic graph of snapshots of your project. Every time you tell Git to record the state of your files, it takes a photograph of the entire project at that moment. That photograph is called a commit. Each commit knows which commit came before it, forming an unbreakable chain of history stretching back to your very first file.

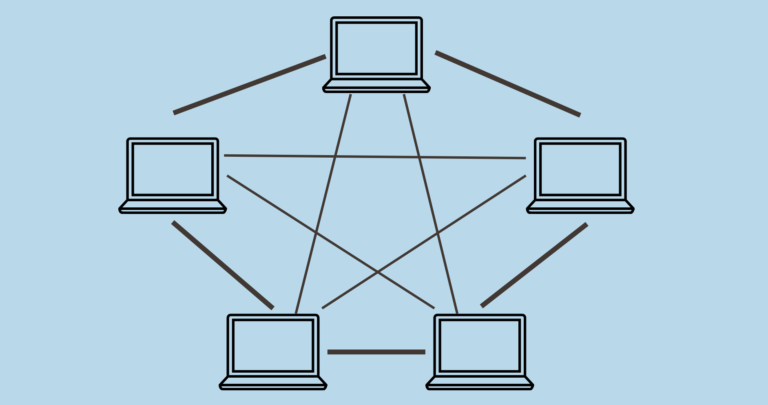

Crucially, Git is completely decentralized. Unlike older version control systems (Subversion, CVS) that required a central server, every Git repository is a complete, standalone copy of the entire project history. This means you can use Git on your local machine for weeks, creating dozens of commits, with no internet connection whatsoever. The “cloud” (GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket) is optional—it’s just someone else’s computer hosting a copy for collaboration and backup.

The Three Trees of Git:

At any given moment, Git maintains three distinct states of your project:

The Working Directory: This is what you see in your file explorer. The files you’re actively editing. Git does nothing to these files automatically.

The Staging Area (Index): This is the “dressing room.” You selectively place files here to prepare them for a snapshot. It allows you to commit only part of your changes—perhaps fixing two bugs but only committing one with its documentation.

The Repository (Commit History): This is the permanent record. When you create a commit, Git takes the exact state of the files in the staging area, packages it with your name, email, timestamp, and commit message, and stores it permanently in the repository.

This three-tree architecture is the single most important concept to grasp. Most Git confusion stems from not understanding the distinction between “I saved my file” and “I committed my file to history.”

Part 2: Your First Repository—From Zero to Commit

Let’s build your first repository from scratch. Open a terminal and create a new directory:

mkdir my-first-repo cd my-first-repo

Step 1: Initialize the Repository

git initThis creates a hidden .git folder. This folder is the repository. It contains the entire history, all commits, all branches, everything. Deleting this folder destroys your version history (but leaves your current files untouched).

Step 2: Create a File

Create hello.txt with the content “Hello, version control!”

Step 3: Check Your Status

git statusGit will report that hello.txt is untracked. Git sees the file but isn’t watching it yet. You need to explicitly tell Git which files matter.

Step 4: Stage the File

git add hello.txt

Now git status shows the file is staged for commit. It’s in the staging area, ready to be permanently recorded.

Step 5: Commit the File

git commit -m "Initial commit: add hello.txt"

Congratulations. You’ve just created a permanent, timestamped, authored snapshot of your project. This commit exists forever in your repository’s history.

Step 6: View Your History

git logYou’ll see your commit, with its unique 40-character hash (e.g., a1b2c3d...), your name, the date, and your message. This hash is the fingerprint of that exact state of your project.

Part 3: The Daily Workflow—A Rhythm, Not a Chore

Once you understand the three-tree model, the daily Git workflow becomes a simple, rhythmic pattern:

Work. Edit files. Create files. Delete files.

Stage.

git add <file>to move specific changes to the staging area.Commit.

git commit -m "message"to permanently record the staged snapshot.Repeat.

That’s it. You can do this all day, on a plane, in a coffee shop, offline. Each commit is a checkpoint you can return to.

Useful shortcuts:

git add .stages all changes in the current directory (be careful—this includes everything).git add -pstages parts of a file interactively. This is a superpower for keeping commits focused.git commit -am "message"combinesgit add(for already tracked files) andgit commitin one command. It skips the staging area entirely.

Part 4: Traveling Through Time—Checking Out the Past

The real magic begins when you need to revisit yesterday, last week, or last year.

To see what a file looked like in a previous commit:

git log --oneline # See commits with short hashes git show a1b2c3d:hello.txt # View hello.txt as it was in commit a1b2c3d

To temporarily travel back in time and explore the entire project as it was:

git checkout a1b2c3dYour working directory instantly transforms to match the exact state of the project at that commit. You can look around, compile the code, run tests. When you’re done exploring:

git checkout main # Return to the present

To permanently revert a file to an earlier version:

git checkout a1b2c3d -- hello.txtThis replaces hello.txt in your working directory with its version from commit a1b2c3d. Stage and commit this change, and the “revert” becomes part of your history.

Part 5: Branching—The Killer Feature

If commits are time travel, branches are parallel universes.

A branch is simply a movable pointer to a specific commit. When you create a new branch, you’re creating a separate timeline of development. You can experiment wildly, break things, and it won’t affect the main branch (or anyone else).

Why branches change everything:

Experiment without fear. Try a radical redesign. If it fails, delete the branch. If it works, merge it back.

Isolate work. Fix a critical bug on a

hotfixbranch while continuing feature development onfeature-login.Enable collaboration. Multiple developers work on separate branches, merging only when ready.

Essential branch commands:

git branch # List all branches git branch feature-x # Create a new branch called feature-x git checkout feature-x # Switch to that branch git checkout -b feature-y # Create and switch in one command

The merge: When your feature is complete, you bring it back into the main timeline:

git checkout main git merge feature-x

Git attempts to automatically integrate the changes from feature-x into main. If two people modified the same lines of the same file differently, Git pauses and asks you to resolve the merge conflict—manually decide which version is correct.

Merge conflicts are not failures; they’re communication. Git has done the tedious work of combining everything that didn’t conflict and is now asking for your expertise on the ambiguous parts. Resolve them, stage the resolved files, and git commit to finalize the merge.

Part 6: Remote Repositories—Collaboration Without Chaos

A remote is another copy of your repository, usually hosted on a server. GitHub, GitLab, and Bitbucket are the most common hosts.

The collaboration pattern:

Clone an existing repository to your local machine.

bashgit clone https://github.com/username/project.gitPull the latest changes from the remote before starting work.

bashgit pull origin mainWork, stage, commit locally (as before).

Push your commits to the remote so others can access them.

bashgit push origin main

The crucial insight: git pull is actually two operations: git fetch (download new commits from the remote) followed by git merge (integrate them into your local branch).

Part 7: The Beginner’s Cheat Sheet—Commands You’ll Actually Use

| Situation | Command |

|---|---|

| Start tracking a project | git init |

| Get a copy of an existing project | git clone <url> |

| See what’s changed since last commit | git status |

| Stage a file for commit | git add <file> |

| Commit staged changes | git commit -m "message" |

| Commit all tracked files (skip staging) | git commit -am "message" |

| View commit history | git log --oneline --graph |

| Create and switch to new branch | git checkout -b <branch> |

| Switch branches | git checkout <branch> |

| Merge a branch into current branch | git merge <branch> |

| Download commits from remote | git pull |

| Upload commits to remote | git push |

| Discard changes in working directory | git restore <file> |

| Unstage a file (keep changes) | git restore --staged <file> |

Part 8: Common Beginner Mistakes—And How to Escape

Mistake 1: Committing large, unrelated changes together.

Fix: Use git add -p to stage only specific hunks of changes. Keep commits focused on a single logical change.

Mistake 2: Writing unhelpful commit messages.

Bad: “fix stuff”

Good: “Fix null pointer exception when user submits empty form”

The rule: A commit message should complete the sentence “If applied, this commit will…”

Mistake 3: Committing sensitive data (passwords, API keys).

Fix: If it’s already pushed, assume it’s compromised. Rotate the credentials immediately. Removing it from history is complex (git filter-branch or BFG Repo-Cleaner) and requires force-pushing, which breaks everyone else’s history.

Mistake 4: Being afraid of the command line.

Git GUIs (GitKraken, Sourcetree, GitHub Desktop) are perfectly valid. However, understanding the underlying model makes any GUI infinitely more comprehensible.

Part 9: The Mindset Shift—Git as a Communication Tool

The ultimate purpose of version control is not technical—it’s human.

Every commit message is a letter to your future self and your teammates. It answers the question: “Why did you do this?” not “What did you do?” (the code shows the what).

Every well-named branch communicates intent: feature/user-authentication tells everyone what you’re working on without asking.

Every pull request (or merge request) is a structured conversation about proposed changes, complete with line-by-line commentary.

Git, at its best, transforms software development from solitary coding into a disciplined, transparent, collaborative craft. It imposes a useful friction—you cannot change history without leaving traces—that encourages thoughtfulness and accountability.

Your Next Steps

Create a throwaway repository today. Not for a real project. Just for experimentation. Create files, make commits, delete them, create branches, merge them, create merge conflicts on purpose and resolve them. Break it. Fix it. The repository is free; your confidence is priceless.

Write a commit message that explains why. Not “updated file” but “increase timeout threshold to prevent timeout errors during peak traffic.”

Make a commit every 15-30 minutes of focused work. Each commit is a save point. You can always squash related commits later before sharing.

Use branches for everything. Even when working alone. Create a branch for each new feature or bug fix. Merge it when complete. This builds muscle memory for when you collaborate with others.

Conclusion: The Most Valuable Skill You Didn’t Know You Needed

Git is not easy. Its command-line interface is often criticized as cryptic and unintuitive. Its model—the directed acyclic graph, the three trees, the detached HEAD state—requires genuine cognitive effort to internalize.

But this difficulty is a feature, not a bug. Git’s complexity reflects the complexity of collaborative creation itself. The tool asks you to be precise, intentional, and communicative. In return, it offers something extraordinary: the ability to work on anything, with anyone, anywhere, without fear.

Version control is not just for software. Writers use it to track revisions of manuscripts. Designers use it to manage branding assets. Scientists use it to document computational experiments. Lawyers use it to collaborate on complex contracts. Anyone who creates digital artifacts—anyone whose work evolves over time—benefits from understanding these principles.

Git won’t make you a better programmer overnight. But it will make you a more confident, more collaborative, and more disciplined creator. And in a world where nearly every significant human achievement is now built on collaborative digital creation, that might be the most valuable skill of all.

OTHER POSTS