How Does Solid-State Storage (SSD) Differ from a Hard Drive (HDD)?

How Does Solid-State Storage (SSD) Differ from a Hard Drive (HDD)?

Two Worlds, One Purpose

If you have purchased a computer in the last five years, you have almost certainly benefited from a quiet revolution. Your laptop boots in seconds, applications launch instantly, and the machine is dead silent. This is the work of the Solid-State Drive (SSD) . Yet, if you have ever needed to store a massive collection of photos, videos, or game libraries without spending a fortune, you may have encountered its aging counterpart: the Hard Disk Drive (HDD) .

Both devices store your data permanently. Both connect to your computer via the same interfaces. To the operating system, they appear functionally identical. But beneath the surface, they are technological opposites.

The HDD is a masterpiece of 20th-century electromechanical engineering—tiny magnetic platters spinning at thousands of revolutions per minute, with read/write heads that hover nanometers above the surface. The SSD is a pure product of the semiconductor age—no moving parts, no spinning, no noise. Just transistors, carefully arranged to trap electrons in floating gates .

Understanding the difference between these two technologies is not merely academic. It determines how fast your computer feels, how long your battery lasts, how safe your data is during a fall, and how much storage you can afford. This guide will take you from the atomic level to the practical purchasing decision, explaining exactly how SSDs and HDDs work and why their differences matter.

Part 1: The Hard Disk Drive – Precision Mechanics at Scale

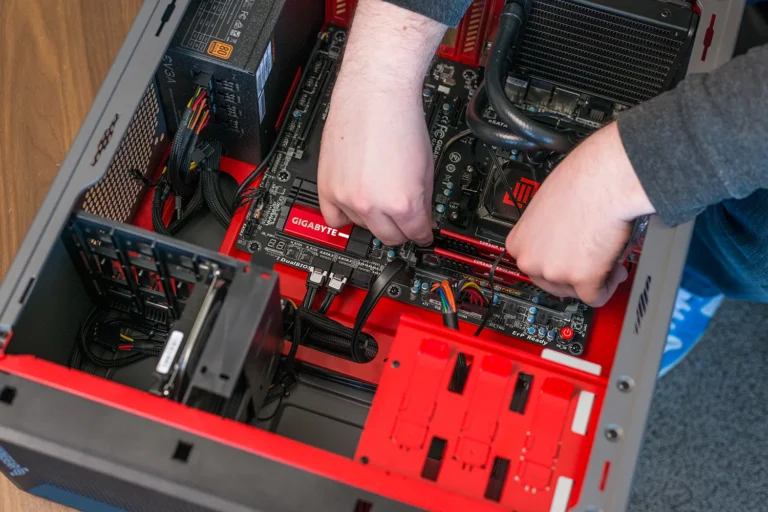

1.1 The Physical Architecture

A hard disk drive is, at its core, a record player with nanometer precision—except it also writes the records.

Inside every HDD, you will find one or more rigid platters, typically made of aluminum or glass, coated with a thin magnetic film . These platters are mounted on a spindle and rotated by a motor at speeds ranging from 5,400 to 15,000 revolutions per minute. Common consumer drives spin at 5,400 or 7,200 RPM .

Suspended just above each platter surface is a read/write head attached to an actuator arm. This arm moves the head radially across the disk, positioning it over the precise location where data is to be read or written. The head does not touch the platter—it “flies” on a microscopic cushion of air created by the spinning motion. The gap is measured in nanometers; if the head touches the platter (a “head crash”), the drive is often permanently damaged .

1.2 How Data Is Written and Read

Data is stored by magnetizing tiny regions of the magnetic coating in specific orientations. During a write operation, an electrical current in the head’s coil generates a magnetic field that aligns the magnetic domains of the media in one of two directions, representing binary 0 or 1 .

Reading is accomplished through magnetoresistive (MR) or giant magnetoresistive (GMR) sensors. These sensors change their electrical resistance in the presence of a magnetic field. As the disk spins beneath the head, the changing magnetic fields from the recorded bits alter the sensor’s resistance, producing a measurable electrical signal that is decoded into data .

The development of GMR heads in the 1990s was a watershed moment; it enabled the dramatic increases in areal density that made multi-terabyte consumer drives possible. The 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg for their discovery of GMR .

1.3 Data Organization

Data on a hard disk is organized into three hierarchical structures :

Tracks: Concentric circles on each platter surface.

Sectors: Divisions within each track, typically 512 bytes or 4,096 bytes (4K) in modern drives.

Cylinders: The set of identical track positions across all platter surfaces.

To read or write a specific piece of data, the drive must perform two mechanical actions:

Seek time: The actuator moves the head arm to the correct track.

Rotational latency: The drive waits for the spinning platter to rotate the correct sector under the head.

These mechanical delays are the fundamental bottleneck of HDD performance. Even the fastest enterprise HDD cannot overcome the physics of moving mass and waiting for rotation.

1.4 The Fragmentation Problem

Because data cannot always be written in contiguous sectors, files on a hard disk often become fragmented—spread across multiple non-adjacent locations. Reading a fragmented file requires the head to jump repeatedly between tracks, incurring additional seek delays. While modern operating systems perform background defragmentation, the susceptibility to fragmentation remains an inherent weakness of rotating media .

Part 2: The Solid-State Drive – Electrons in a Cage

2.1 The Fundamental Shift

The SSD represents a complete departure from electromechanical storage. It has no moving parts. It is, essentially, a very large, very sophisticated USB flash drive—but with vastly improved performance, reliability, and addressing capabilities .

At its heart, an SSD consists of three main components:

NAND flash memory chips: Where the data is physically stored.

A controller: A specialized processor that manages data placement, wear leveling, error correction, and communication with the host computer.

DRAM cache (optional, but common): Used for mapping tables and temporary data buffering.

2.2 The Floating Gate Transistor

The magic of NAND flash resides in a special type of transistor called a floating-gate MOSFET .

In a conventional transistor, a voltage applied to the control gate determines whether current flows between source and drain. In a floating-gate transistor, there is an additional conductive layer—the floating gate—completely surrounded by an insulating oxide layer. This floating gate is electrically isolated; it has no direct connection to any other component.

Here is the key insight: Electrons can be forced into or pulled out of this isolated floating gate through a quantum mechanical phenomenon called Fowler-Nordheim tunneling. Once the electrons are in the floating gate, they remain trapped indefinitely because the surrounding oxide prevents their escape. The presence or absence of this trapped charge alters the transistor’s threshold voltage—the voltage that must be applied to the control gate to make the transistor conduct .

To read a cell: A reference voltage is applied to the control gate. If the floating gate contains charge (representing a 0), the transistor requires a higher voltage to turn on and remains off. If the floating gate is empty (representing a 1), the transistor turns on and current flows. This current is detected and interpreted as data .

To write (program) a cell: A high voltage (typically ~20V) is applied, forcing electrons through the oxide layer and into the floating gate. This is a “write 0” operation.

To erase a cell: A high voltage of opposite polarity is applied, pulling electrons out of the floating gate and resetting it to the “1” state.

Crucially, flash memory cannot overwrite existing data. A cell containing a 0 must be erased (reset to 1) before it can be programmed again. However, erasure can only be performed on entire blocks (often several megabytes), not individual cells. This erase-before-write requirement drives much of the complexity in SSD controllers .

2.3 NAND Flash Architecture

There are two primary ways to organize flash memory cells into arrays: NOR and NAND. For mass storage, NAND flash is universal because it achieves much higher densities at lower cost .

In a NAND flash array, transistors are connected in series strings (typically 32 to 256 cells per string). This series connection dramatically reduces the number of bit-line contacts, enabling higher density. However, it also means that individual cells cannot be read or written directly; instead, data is accessed in pages (typically 4KB to 16KB), and erased in blocks (typically several megabytes) .

This page/block architecture is fundamental to understanding SSD performance and longevity.

2.4 Cell Types: SLC, MLC, TLC, QLC

A single-level cell (SLC) stores one bit of data: either charged (0) or uncharged (1). However, by precisely controlling the amount of charge in the floating gate, a cell can represent more than two states :

| Cell Type | Bits per Cell | States per Cell | Typical Endurance (P/E Cycles) | Relative Speed | Relative Cost per GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC | 1 | 2 | ~100,000 | Fastest | Highest |

| MLC | 2 | 4 | ~3,000–5,000 | ↓ | ↓ |

| TLC | 3 | 8 | ~1,000 | ↓ | ↓ |

| QLC | 4 | 16 | ~300–1,000 | Slowest | Lowest |

Sources:

The progression from SLC to QLC represents a direct trade-off: capacity and cost versus performance and endurance. Writing to a TLC or QLC cell requires much finer voltage control than SLC, making writes slower. The narrower voltage windows also make these cells more susceptible to charge leakage and read disturbance, necessitating more powerful error correction.

3D NAND (also called V-NAND) is a transformative innovation that stacks memory cells vertically in dozens of layers, dramatically increasing density without shrinking the individual cells. This mitigates many of the endurance and performance penalties associated with planar TLC/QLC .

Part 3: Head-to-Head Comparison – 2025 Edition

With the fundamental technologies established, we can now examine how SSDs and HDDs compare across every meaningful metric.

3.1 Performance

This is the SSD’s uncontested victory. The absence of mechanical movement means near-instantaneous access to any data location.

| Metric | SSD (2025) | HDD (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential Read | Up to 7,450 MB/s (PCIe 5.0) | ~270 MB/s (7200 RPM) |

| Sequential Write | Up to 6,900 MB/s | ~250 MB/s |

| Random Read (4K) | Up to 1.4 million IOPS | Typically <500 IOPS |

| Boot Time (Windows) | 5–10 seconds | 30–60 seconds |

| Application Launch | Instantaneous | Noticeable delay |

| File Transfer (Large) | 10–30 seconds per GB | 3–5 seconds per GB |

Sources:

Why the difference? An HDD must physically move a head to the correct track and wait for the platter to rotate to the correct sector—tens of milliseconds per random access. An SSD can access any cell in tens of microseconds. This three-order-of-magnitude advantage in random access is why an SSD-equipped computer feels fundamentally faster, regardless of CPU or RAM.

Expert perspective: “Unless you frequently copy large files, a modern SSD will provide several times better performance than any hard drive. Thus, utterly outperform HDDs in terms of system responsiveness.”

3.2 Capacity

| Metric | SSD (2025) | HDD (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Consumer Capacity | 8 TB (common) | 24 TB (available) |

| Max Enterprise Capacity | 64+ TB | 30–60 TB |

| Typical Sweet Spot | 500 GB – 2 TB | 4 TB – 16 TB |

Sources:

HDDs continue to lead in absolute maximum capacity and availability of very high capacity drives at reasonable prices. An 8TB HDD is a standard consumer product; an 8TB SSD is a premium component. This is the primary reason HDDs remain relevant for mass storage applications.

3.3 Cost per Gigabyte

| Metric | SSD (2025) | HDD (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Approximate Cost per GB | $0.10 – $0.15 | $0.03 – $0.06 |

| 1TB Drive Price (Approx.) | $90 – $100 | $40 – $50 |

| 8TB Drive Price (Approx.) | $800 – $1,200 | $150 – $250 |

Sources:

The gap is closing, but it remains significant. SSD prices have fallen dramatically over the past decade, but on a per-terabyte basis, HDDs remain the clear economic choice for bulk storage. For archival and backup purposes, the cost advantage of HDDs is compelling.

3.4 Physical Durability and Reliability

| Metric | SSD | HDD |

|---|---|---|

| Moving Parts | None | Spinning platters, moving actuator |

| Shock Resistance | Excellent (no mechanical damage risk) | Poor (heads can contact platters) |

| Vibration Sensitivity | None | Significant |

| Noise | Silent | Audible spin and seek clicks |

| Heat Generation | Low (2–5W active) | Moderate (6–9W active) |

| Power Consumption (Idle) | As low as 0.05W | 3–5W |

Sources:

The SSD is fundamentally more durable because there is nothing to break. A laptop with an SSD can be dropped during operation with a high probability of survival; a laptop with an HDD faces near-certain head crash and data loss. This is why SSDs are universal in modern portable devices.

3.5 Longevity and Failure Modes

This is where the comparison becomes nuanced. Both drives fail, but they fail differently.

| Metric | SSD | HDD |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Failure Mechanism | Write cycle exhaustion, controller failure | Mechanical wear, head crash, motor failure |

| Typical Lifespan | 5–10 years (write-limited) | 3–5 years (mechanical) |

| Failure Onset | Often sudden, catastrophic | Often gradual (bad sectors, slow performance, noises) |

| Annual Failure Rate | ~0.98% (Backblaze data) | ~1.64% (Backblaze data) |

| Data Recovery | Difficult to impossible in controller failure | Often possible with specialized cleanroom services |

Sources:

Critical insight: SSDs fail less often overall, but their failures can be more devastating. An HDD often provides warning signs—clicking sounds, gradual slowdown, file corruption—that allow proactive data backup. An SSD can be perfectly functional one moment and completely unresponsive the next, particularly if the controller fails .

Write endurance is real but increasingly irrelevant for consumers. A modern TLC SSD with 1,000 P/E cycles can write hundreds of terabytes before exhaustion. For typical office, web, and media use, this represents a lifespan measured in decades. Only professional workloads involving continuous massive writes (video surveillance, database transaction logs, scientific data acquisition) are likely to wear out a consumer SSD within its useful life .

3.6 Fragmentation and Maintenance

HDDs benefit from, and may require, defragmentation. As files become scattered across the platter, read performance degrades. Windows automatically defragments HDDs on a schedule .

SSDs do not require defragmentation and are harmed by it. The lack of mechanical positioning means access time is uniform across the entire storage space. Moreover, defragmentation involves massive rewriting of data, which consumes write endurance unnecessarily. Modern operating systems recognize SSDs and disable automatic defragmentation .

Part 4: The Technology Comparison Summary Table

| Attribute | Solid-State Drive (SSD) | Hard Disk Drive (HDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | NAND flash memory (floating-gate transistors) | Magnetic recording on spinning platters |

| Moving Parts | None | Yes (spindle motor, actuator arm) |

| Access Time | ~0.1 ms (microseconds) | ~5–15 ms (milliseconds) |

| Sequential Read Speed | 500–7,450 MB/s (SATA to PCIe 5.0) | 80–270 MB/s (5400–7200 RPM) |

| Random Read IOPS | >100,000 (up to 1.4M) | <500 |

| Capacity Range (Consumer) | 128 GB – 8 TB | 500 GB – 24 TB |

| Cost per GB | Higher (~$0.10–0.15) | Lower (~$0.03–0.06) |

| Shock Resistance | Excellent (no mechanical components) | Poor (fragile moving parts) |

| Noise | Silent | Audible (spinning, clicking) |

| Power Consumption (Active) | 2–5 W | 6–9 W |

| Power Consumption (Idle) | <0.1 W | 3–5 W |

| Heat Generation | Low | Moderate |

| Operating System Boot Time | 5–15 seconds | 30–60 seconds |

| Fragmentation Impact | None | Significant |

| Primary Failure Mode | Write cycle exhaustion, controller failure | Mechanical wear, head crash |

| Typical Lifespan | 5–10 years | 3–5 years |

| Data Recovery Complexity | High (especially controller failure) | Moderate (cleanroom recovery often possible) |

| Ideal Use Case | OS, applications, active projects, laptops | Bulk storage, backups, media libraries, servers |

Sources: Compiled from

Part 5: Making the Choice – Which Drive for Which Job?

The question is no longer “SSD or HDD?” It is “How should I combine them?”

5.1 The Universal Recommendation: Hybrid Storage

For any desktop PC, and for any laptop that supports two drives (or a single drive plus external storage), the optimal configuration is:

An SSD for the operating system, applications, and active projects.

This is where you feel performance. Boot times, application launches, file searches—all are transformed by the SSD.

Recommended capacity: 500 GB – 2 TB, depending on your application footprint.

An HDD (internal or external) for mass storage, media libraries, and backups.

Photos, videos, documents, game libraries that you are not actively playing, system backups—these benefit minimally from SSD speeds.

Recommended capacity: 4 TB – 20+ TB, depending on your archive size.

This hybrid approach delivers 95% of the performance benefit of an all-SSD system at 50% of the cost .

5.2 When to Choose SSD-Only

Laptops: Virtually all modern laptops are SSD-only because HDDs are too bulky, fragile, and power-hungry for portable use.

Performance-critical workstations: Video editing, software compilation, large dataset analysis—if your workflow is I/O-bound, every millisecond counts.

Silence-required environments: Recording studios, home theaters, libraries.

Any device that will be moved frequently: The shock resistance of SSDs is non-negotiable for mobile use .

5.3 When to Choose HDD-Only

Network-Attached Storage (NAS): For file servers and media servers, capacity per dollar is paramount, and mechanical drives are adequate.

Cold storage / backup archives: Data written once and read rarely.

Extreme budget constraints: If you need 4TB of storage for under $100, HDD is your only option.

5.4 Professional Profiles

| User Type | Primary Drive | Secondary / Bulk Storage |

|---|---|---|

| General Office / Web / Email | 256–512 GB SSD | Optional external HDD for backups |

| Gamer | 1–2 TB SSD (for current games) | 4–8 TB HDD (for game library, media) |

| Photographer / Videographer | 1–2 TB SSD (for active projects) | 8–20 TB HDD / RAID (for archive) |

| Developer | 512 GB – 1 TB SSD | 2–4 TB HDD (for VMs, build artifacts) |

| Data Hoarder / Home Server | 256–512 GB SSD (boot) | 20+ TB HDD array |

Source:

Part 6: The Future – Convergence or Continued Coexistence?

The trajectory is clear but the endpoint is not.

SSDs will continue to capture market share. As NAND manufacturing scales to ever-higher layer counts (200+ layers in production, 500+ in development) and cell types evolve beyond QLC to PLC (penta-level, 5-bit/cell), the cost per gigabyte of SSDs will continue its downward march. The performance gap is so vast that, at price parity, the HDD ceases to exist in consumer markets.

However, fundamental physics favors HDDs for the highest capacities. The areal density of magnetic recording continues to advance through technologies like heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) and microwave-assisted magnetic recording (MAMR). Seagate and Western Digital have demonstrated 30+ TB drives and are targeting 50+ TB and beyond. There remains a point on the cost curve where magnetic recording is simply less expensive per bit than trapping electrons in floating gates .

The likely future is a bifurcated market:

Consumer and performance computing: Nearly 100% SSD.

Hyperscale data centers and mass storage: HDDs for warm/cold data, SSDs for hot data and caching.

Conclusion: Two Technologies, One Goal

The Hard Disk Drive is a miracle of mechanical engineering—billions of moving parts operating in nanometer proximity, manufactured for pennies per gigabyte. It served computing faithfully for six decades.

The Solid-State Drive is a miracle of semiconductor physics—quantum tunneling harnessed for consumer storage, delivering performance that would have seemed impossible a generation ago.

They are not enemies. They are complementary tools for different jobs. The SSD provides the speed and responsiveness that make modern computing feel effortless. The HDD provides the vast, affordable reservoirs where our accumulating digital lives can rest.

The question is not which technology is “better.” It is whether you have matched the right tool to the right task.

For the operating system, applications, and active work—choose the SSD. For the archive, the backup, the media library—the HDD remains an entirely rational choice.

Understand the difference, and you will never waste money on storage again.

OTHER POSTS