IP Addressing

IP Addressing: The Complete Guide to Internet Protocol Addressing

Introduction: The Digital Postal System of the Internet

Every device connected to the internet—from smartphones to servers, smart refrigerators to supercomputers—requires a unique identifier to communicate, just as every house needs a unique address to receive mail. This digital addressing system, known as Internet Protocol (IP) addressing, forms the fundamental infrastructure that enables global connectivity. This comprehensive guide explores the architecture, evolution, implementation, and future of IP addressing, the invisible framework that makes the modern internet possible.

Section 1: The Foundation – What is an IP Address?

Definition and Purpose

An Internet Protocol (IP) address is a numerical label assigned to each device participating in a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication. It serves two primary functions:

Host or network interface identification

Location addressing (providing a means to find the device on the network)

The Analogy: Physical vs. Digital Addressing

Physical World Digital World --------------- --------------- Street Address: 123 Main St. IP Address: 192.168.1.10 City: Anytown Network: 192.168.1.0/24 ZIP Code: 12345 Subnet Mask: 255.255.255.0 Country: USA Default Gateway: 192.168.1.1

Core Characteristics

Uniqueness: Each IP address must be unique within its network scope

Hierarchical structure: Organized for efficient routing

Dual role: Identifies both the network and the specific host

Temporary or permanent: Can be static or dynamically assigned

Section 2: The Evolution – From IPv4 to IPv6

IPv4: The Foundation (1981-Present)

Structure and Format:

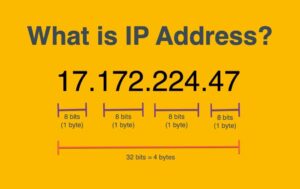

32-bit address: 4 octets separated by periods (dotted-decimal notation)

Example: 192.168.1.1

Total addresses: 2³² = 4,294,967,296 (approximately 4.3 billion)

Binary representation: 11000000.10101000.00000001.00000001

The IPv4 Exhaustion Crisis:

Depletion timeline: Final /8 blocks allocated in 2011

Root cause: Exponential internet growth unanticipated in 1970s design

Regional exhaustion: APNIC (2011), RIPE NCC (2012), LACNIC (2014)

Current status: Commercially available but at premium prices

IPv6: The Solution (1998-Present)

Structure and Format:

128-bit address: 8 groups of 4 hexadecimal digits separated by colons

Example: 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

Compressed form: 2001:db8:85a3::8a2e:370:7334 (leading zeros omitted, :: for consecutive zeros)

Total addresses: 2¹²⁸ ≈ 340 undecillion (3.4×10³⁸)

Adequacy: Approximately 665×10²¹ addresses per square meter of Earth’s surface

Key Improvements over IPv4:

Vast address space: Effectively unlimited for foreseeable future

Simplified header: Fixed length, optimized for processing

Built-in security: IPsec implementation is mandatory

Auto-configuration: Stateless address configuration (SLAAC)

Efficient routing: Hierarchical addressing reduces routing table size

Better multicast: Native support without workarounds

IPv6 Address Types:

Unicast: One-to-one communication (global, link-local, unique-local)

Multicast: One-to-many communication

Anycast: One-to-nearest communication (multiple devices share address)

Current Adoption Status (2024):

Global average: ~40% of users access Google via IPv6

Leading countries: India (~70%), Germany (~65%), USA (~50%)

Major providers: Comcast, Verizon, T-Mobile have extensive deployment

Challenges: Legacy equipment, knowledge gaps, dual-stack complexity

Section 3: IPv4 Addressing in Depth

Address Classes (Historical but Influential)

Classful Addressing (Pre-CIDR):

Class A: 0.0.0.0 - 127.255.255.255 • First octet: 0-127 • Network/Host: N.H.H.H • Subnet mask: 255.0.0.0 (/8) • Networks: 128 (0-127, but 0 and 127 reserved) • Hosts per network: 16,777,214 Class B: 128.0.0.0 - 191.255.255.255 • First octet: 128-191 • Network/Host: N.N.H.H • Subnet mask: 255.255.0.0 (/16) • Networks: 16,384 • Hosts per network: 65,534 Class C: 192.0.0.0 - 223.255.255.255 • First octet: 192-223 • Network/Host: N.N.N.H • Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0 (/24) • Networks: 2,097,152 • Hosts per network: 254 Class D: 224.0.0.0 - 239.255.255.255 (Multicast) Class E: 240.0.0.0 - 255.255.255.255 (Experimental)

Limitations of Classful Addressing:

Rigid boundaries: Wasted address space (company needing 300 hosts got Class B with 65k addresses)

Routing table explosion: Each network required separate entry

Inefficient allocation: Led to rapid IPv4 exhaustion

CIDR: Classless Inter-Domain Routing (1993)

The Solution to Classful Limitations:

Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM): Subnets of different sizes within same network

CIDR notation: IP address followed by slash and prefix length (192.168.1.0/24)

Route aggregation: Multiple networks advertised as single route

Efficient allocation: ISPs get blocks they can subnet appropriately

CIDR Notation Examples:

192.168.1.0/24: 256 addresses (192.168.1.0 – 192.168.1.255)

10.0.0.0/8: 16,777,216 addresses (entire 10.x.x.x range)

172.16.0.0/12: 1,048,576 addresses (172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255)

Special and Reserved IPv4 Addresses

Private Address Ranges (RFC 1918):

10.0.0.0/8: Single Class A network

172.16.0.0/12: 16 contiguous Class B networks

192.168.0.0/16: 256 contiguous Class C networks

Purpose: Not routable on public internet, used behind NAT

Other Special Addresses:

Loopback: 127.0.0.0/8 (typically 127.0.0.1)

Link-local: 169.254.0.0/16 (APIPA – Automatic Private IP Addressing)

Multicast: 224.0.0.0/4

Limited broadcast: 255.255.255.255

Documentation/Examples: 192.0.2.0/24, 198.51.100.0/24, 203.0.113.0/24

Section 4: Subnetting – The Art of Network Division

Binary Foundation

Decimal to Binary Conversion:

192 = 11000000 168 = 10101000 1 = 00000001 0 = 00000000 Subnet Mask 255.255.255.0 = 11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000 CIDR /24 = 24 network bits, 8 host bits

Subnetting Process

Step-by-Step Example: Creating subnets from 192.168.1.0/24

Requirements:

5 departments needing: 50, 25, 20, 10, and 5 hosts respectively

Efficient allocation with room for growth

Solution:

List requirements in descending order: 50, 25, 20, 10, 5

Calculate needed host bits: 2ʰ – 2 ≥ hosts required

50 hosts: 2⁶ – 2 = 62 (needs 6 host bits, /26 subnet)

25 hosts: 2⁵ – 2 = 30 (needs 5 host bits, /27 subnet)

etc.

Allocate sequentially:

Network: 192.168.1.0/24 Subnet 1: 192.168.1.0/26 (50 hosts) • Range: 192.168.1.0 - 192.168.1.63 • Usable: 192.168.1.1 - 192.168.1.62 • Broadcast: 192.168.1.63 Subnet 2: 192.168.1.64/27 (25 hosts) • Range: 192.168.1.64 - 192.168.1.95 • Usable: 192.168.1.65 - 192.168.1.94 • Broadcast: 192.168.1.95 Subnet 3: 192.168.1.96/27 (20 hosts, same as above) Subnet 4: 192.168.1.128/28 (10 hosts) Subnet 5: 192.168.1.144/29 (5 hosts)

Subnetting Cheat Sheet

CIDR Subnet Mask Hosts Networks from /24 ---- ----------- ----- ----------------- /25 255.255.255.128 126 2 /26 255.255.255.192 62 4 /27 255.255.255.224 30 8 /28 255.255.255.240 14 16 /29 255.255.255.248 6 32 /30 255.255.255.252 2 64 (Point-to-point) /31 255.255.255.254 2* 128 (RFC 3021, no broadcast) /32 255.255.255.255 1 256 (Single host route)

/31 is special case for point-to-point links

Section 5: IP Address Allocation and Management

The Global Hierarchy

Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA):

Role: Global coordinator of IP addressing

Function: Allocates blocks to Regional Internet Registries (RIRs)

Parent organization: ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers)

Regional Internet Registries (RIRs):

AFRINIC: Africa

APNIC: Asia-Pacific

ARIN: United States, Canada, Caribbean

LACNIC: Latin America and Caribbean

RIPE NCC: Europe, Middle East, Central Asia

National Internet Registries (NIRs):

Country-specific organizations (e.g., CNNIC in China, KISA in Korea)

Local Internet Registries (LIRs):

Typically Internet Service Providers (ISPs)

End Users: Organizations and individuals

Allocation Process Example

IANA → RIR (APNIC) → NIR (JPNIC) → LIR (ISP) → Business Customer → Department → Host

Public vs. Private Addressing

Public IP Addresses:

Globally routable on the internet

Must be unique worldwide

Assigned by RIRs/LIRs

Direct accessibility from anywhere on internet

Private IP Addresses (RFC 1918):

Not routable on public internet

Reusable across different private networks

Require NAT to access internet

Three ranges: 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, 192.168.0.0/16

Dynamic vs. Static Assignment

DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol):

Automatic assignment: IP address, subnet mask, gateway, DNS servers

Lease-based: Temporary assignment (typically 24 hours)

Renewal: Clients automatically request extension

Efficiency: Reuses addresses from pool

Default for: Most end-user devices

Static Assignment:

Manual configuration: Set on device itself

Permanent: Doesn’t change unless manually reconfigured

Use cases: Servers, network equipment, printers

Advantages: Predictable, reliable for services

Disadvantages: Administrative overhead, potential conflicts

APIPA (Automatic Private IP Addressing):

Range: 169.254.0.0/16

Trigger: DHCP failure

Purpose: Local network communication only

Limitation: No internet access

Section 6: NAT – Extending IPv4 Lifespan

Network Address Translation Fundamentals

The NAT Concept:

Multiple private addresses share one or few public addresses

RFC 1918 realization: Private addresses aren’t routable, need translation

Primary benefit: Conserves public IPv4 addresses

Basic NAT Operation:

Private Network NAT Router Public Internet

------------- ---------- ---------------

192.168.1.10:5000 → Translate → 203.0.113.5:6000 → Web Server

↓

192.168.1.11:5000 → Translate → 203.0.113.5:6001 → Web ServerNAT Types

1. Static NAT:

One-to-one fixed mapping

Example: Mail server at 192.168.1.10 always maps to 203.0.113.10

Use: Hosting services from private network

2. Dynamic NAT:

Pool of public addresses shared dynamically

First-come, first-served from pool

Limitation: Number of simultaneous connections ≤ pool size

3. PAT (Port Address Translation) / NAT Overload:

Most common type (home routers use this)

Multiple private addresses map to single public address

Uses port numbers to distinguish connections

Theoretical limit: ~65,000 connections per public IP

4. Carrier-Grade NAT (CGN/LSN):

ISPs use: Multiple customers share public IPs

Double NAT: Customer NAT → ISP NAT → Internet

Controversial: Breaks some applications, privacy concerns

NAT Limitations and Issues

Application Breaking:

IP in payload: FTP, SIP, some gaming protocols

Peer-to-peer: Direct connections difficult

Geo-location: Services see NAT address, not user’s

Performance Impact:

State table maintenance overhead

Connection tracking resource consumption

Mitigation: Hardware acceleration in modern routers

Security Considerations:

Obfuscation: Hides internal network structure

Not a firewall: Often confused with security function

Vulnerabilities: State table exhaustion attacks

Section 7: Practical IP Addressing

Address Planning Best Practices

Enterprise Network Design Example:

Headquarters: 10.0.0.0/16 • Infrastructure: 10.0.0.0/24 (Routers, switches, management) • Servers: 10.0.1.0/24 (Data center) • User VLANs: 10.0.10.0/23 (512 users, /23 = 510 hosts) • Wireless: 10.0.20.0/24 • Guests: 10.0.30.0/24 • IoT: 10.0.40.0/24 • Future: 10.0.50.0/24 - 10.0.100.0/24 Branch Offices: 10.1.0.0/16, 10.2.0.0/16, etc. • Consistent subnetting scheme across locations VPN/Remote: 10.254.0.0/16

Troubleshooting Common Issues

IP Conflict:

Symptoms: Intermittent connectivity, “IP conflict” warnings

Detection:

arp -ashows multiple MACs for same IPResolution: DHCP cleanup, static assignment review

Incorrect Subnet Mask:

Symptom: Can ping some devices but not others in same network

Check: Compare

ipconfig/ifconfigoutput on multiple devicesExample: Computer with 255.255.255.0 can’t reach 255.255.0.0 device

Default Gateway Issues:

Symptom: Local network works, no internet

Test:

ping 8.8.8.8fails,ping local_deviceworksCheck: Gateway IP, gateway connectivity, routing table

DNS vs. IP Problems:

Diagnosis:

ping google.comfails butping 8.8.8.8worksIndicates: DNS configuration issue, not IP addressing

Useful Command-Line Tools

Windows:

ipconfig /all # Display all IP configuration ping 192.168.1.1 # Test connectivity tracert 8.8.8.8 # Trace route path arp -a # Show ARP table nslookup google.com # DNS query

Linux/macOS:

ifconfig or ip addr # Display IP configuration ping 192.168.1.1 # Test connectivity traceroute 8.8.8.8 # Trace route path arp -a # Show ARP table dig google.com # DNS query netstat -rn # Routing table

Section 8: IPv6 Implementation and Transition

IPv6 Address Types and Usage

Global Unicast Address (GUA):

Range: 2000::/3 (2000: – 3fff:)

Structure: Global routing prefix (48 bits) + Subnet ID (16 bits) + Interface ID (64 bits)

Example: 2001:db8:1234:5678::1/64

Link-Local Address:

Range: fe80::/10

Automatically assigned: To every IPv6 interface

Scope: Only valid on local link (not routable)

Example: fe80::1a2b:3c4d:5e6f:1a2b%eth0

Unique Local Address (ULA):

Range: fc00::/7 (similar to IPv4 private addresses)

Not routable on internet: But globally unique

Example: fd00:1234:5678::/48

Multicast Address:

Range: ff00::/8

Well-known examples:

ff02::1: All nodes on local link

ff02::2: All routers on local link

ff02::1:ffxx:xxxx: Solicited-node multicast

IPv6 Address Assignment Methods

Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC):

Process: Router Advertisement (RA) + Interface ID generation

Interface ID: Often derived from MAC address (EUI-64)

Privacy concern: MAC-based addressing allows tracking

Solution: Privacy extensions generate temporary addresses

DHCPv6:

Two modes: Stateful (assigns addresses) and Stateless (other parameters)

Advantage over SLAAC: More control, easier logging

Common in enterprises: Better manageability

Manual Configuration:

Similar to IPv4: Set address, prefix, gateway

Use cases: Servers, routers, critical infrastructure

Transition Technologies

Dual Stack:

Most common approach: Run IPv4 and IPv6 simultaneously

Requirement: Applications must support both

Advantage: Seamless experience based on destination capability

Tunneling:

6in4: IPv6 encapsulated in IPv4 packets

6to4: Automatic tunneling using anycast address

Teredo: IPv6 over UDP through NATs

Advantage: Connect IPv6 islands over IPv4 infrastructure

Translation:

NAT64: IPv6 to IPv4 translation

DNS64: Synthesizes AAAA records from A records

Use case: IPv6-only clients accessing IPv4-only servers

IPv6 Subnetting Simplicity

Standard Practice:

/64 subnets: Standard for most networks

Reason: Required for SLAAC, efficient for router advertisements

Example allocation:

textISP allocation: 2001:db8:1234::/48 Customer networks: • Office LAN: 2001:db8:1234:0001::/64 • WiFi: 2001:db8:1234:0002::/64 • Servers: 2001:db8:1234:0003::/64 • Future: 2001:db8:1234:0004::/64 - ffff::/64

Benefits over IPv4 Subnetting:

No broadcast: Uses multicast instead

No NAT (typically): End-to-end connectivity restored

Auto-configuration: Reduces administrative overhead

Abundant addresses: No need for tight allocation

Section 9: Security Considerations

IP Address-Based Threats

Reconnaissance:

IP scanning: Probing address ranges for active hosts

Service identification: Port scanning discovered hosts

Defense: Firewalls, intrusion prevention, network segmentation

Spoofing:

Source IP forgery: Sending packets with false source address

Uses: DoS amplification, anonymity, bypassing IP-based ACLs

Prevention: Ingress/egress filtering (BCP38/84), uRPF

Amplification Attacks:

Mechanism: Small query generates large response to spoofed victim

Protocols abused: DNS, NTP, SNMP, SSDP

Mitigation: Rate limiting, protocol-specific fixes

Privacy Implications

IP Address as Identifier:

Persistent tracking: Even with dynamic addresses

Geo-location: Typically accurate to city level

Behavioral correlation: Across websites/services

Mitigation Strategies:

VPNs: Mask true IP address

TOR/Onion routing: Multi-layer encryption and routing

ISP practices: Rapid DHCP rotation, IPv6 privacy extensions

Application design: Minimize IP logging, use anonymization

IPv6 Security Considerations

Increased Scanning Difficulty:

Challenge: 2⁶⁴ addresses per subnet makes scanning impractical

But: Addresses often predictable (EUI-64, sequential assignment)

Best practice: Use privacy extensions, random addressing

New Attack Vectors:

Router Advertisement attacks: Spoofed RAs can redirect traffic

Extension header abuse: Could evade security controls

Mitigation: RA Guard, proper firewall rules for IPv6

Dual-Stack Concerns:

Asymmetric security: IPv4 and IPv6 might have different rules

Tunneling risks: Transition technologies create new attack surfaces

Recommendation: Equal security for both protocols

Section 10: Future of IP Addressing

IPv6 Adoption Acceleration

Drivers of Adoption:

Mobile networks: LTE/5G natively IPv6

IoT expansion: Billions of devices need addresses

Cloud providers: Major clouds fully support IPv6

Government mandates: Some require IPv6 capability

Projected Timeline:

2025: Majority of internet traffic over IPv6

2030: IPv4 becomes legacy, maintained for compatibility

Beyond: Possible IPv4 sunsetting in certain segments

New Addressing Models

Segment Routing IPv6 (SRv6):

Concept: Source routing with IPv6 extension headers

Benefits: Simplified network programming, traffic engineering

Status: Emerging in carrier networks

Blockchain-Based Addressing:

Experimental: Self-sovereign identity tied to IP space

Potential: Decentralized address allocation

Challenges: Integration with existing infrastructure

Quantum Computing Implications

Cryptographic Concerns:

Current issue: Public key infrastructure relies on hard math problems

Quantum threat: Shor’s algorithm could break current cryptography

Preparation: Post-quantum cryptography standardization underway

Addressing in Quantum Networks:

Research area: Quantum internet with entanglement-based communication

Different paradigm: May require new addressing concepts entirely

Timeline: Experimental stages currently

Environmental Considerations

Energy Efficiency:

IPv6 advantage: Simplified headers reduce processing

Hardware refresh: Newer IPv6-optimized equipment more efficient

Lifecycle management: Phasing out IPv4-only devices

E-Waste Reduction:

Extended lifespan: Dual-stack capability extends device usefulness

Standardization: Global addressing reduces need for NAT hardware

Resource optimization: Efficient allocation reduces overall hardware needs

Conclusion: The Invisible Foundation of Connectivity

IP addressing represents one of the most elegant yet practical engineering solutions of the digital age—a hierarchical, scalable system that has grown from connecting a few research computers to enabling a global network of billions of devices. Its evolution from the constrained IPv4 to the expansive IPv6 mirrors the internet’s own transformation from academic project to essential global infrastructure.

Understanding IP addressing is more than technical knowledge; it’s literacy in the language of digital connectivity. From network engineers designing global infrastructures to developers creating distributed applications, from security professionals defending networks to policymakers shaping internet governance—all engage with the implications of this fundamental system.

As we move toward an increasingly connected world—with 5G, IoT, edge computing, and eventually quantum networks—the principles of IP addressing will continue to evolve but remain essential. The transition to IPv6, while gradual, represents a necessary step toward sustaining the internet’s growth and innovation potential.

The most successful future networks will be those that leverage the strengths of both IPv4 and IPv6 during the extended transition, while preparing for new addressing paradigms that may emerge. What remains constant is the need for addresses that are both unique identifiers and efficient locators—the dual function that has made IP addressing endure for decades.

In mastering IP addressing, we gain not just technical capability but a deeper understanding of how our connected world is structured—and how we might shape its future architecture. Whether working with the familiar dotted-decimal notation of IPv4 or the hexadecimal colons of IPv6, we’re engaging with a system that, though often invisible to end users, forms the very foundation of our digital lives.