Mesh Networks for Communities: DIY internet infrastructure

Building Your Own Internet: How Community Mesh Networks Are Rewiring the World

In an age where internet access is considered as essential as electricity, a significant portion of the global population remains underserved, overcharged, or outright disconnected. Meanwhile, even in well-connected cities, concerns over privacy, corporate control, and network fragility persist. In response, a grassroots movement is quietly building an alternative: community-owned mesh networks. This is the story of DIY internet infrastructure—a technical solution born from social necessity.

What is a Mesh Network?

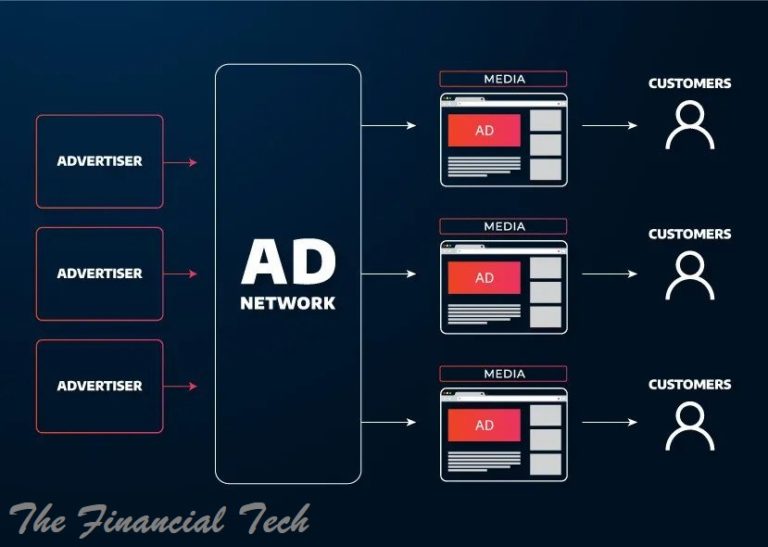

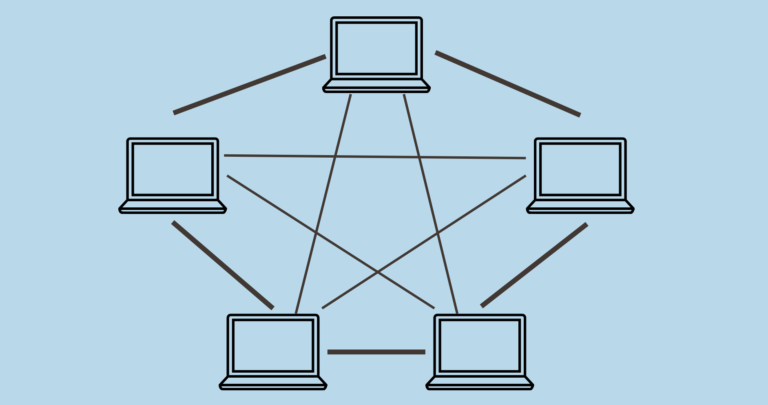

Unlike the traditional, centralized “hub-and-spoke” model of most ISPs (where all data flows through a single point), a mesh network is decentralized. Each device (or node) in the network connects directly to multiple other nodes, creating a resilient, web-like fabric of connectivity.

If one node goes down or a connection is blocked, the network automatically “self-heals” by re-routing data through alternate paths. There is no single point of failure. In a community mesh, these nodes are typically inexpensive wireless routers mounted on rooftops, in windows, or on streetlights, creating a sprawling, cooperative wireless cloud over a neighborhood, town, or city.

The “Why”: Motivations for Building a Community Mesh

Closing the Digital Divide: In rural, remote, or low-income urban areas, large ISPs often decline to build costly infrastructure. Communities can take matters into their own hands, building their own network to provide affordable, basic connectivity.

Resilience and Disaster Response: During natural disasters, centralized internet and cell networks often fail. Mesh networks, powered by solar batteries and independent of telco infrastructure, can keep local communication alive for coordination and emergency alerts. This was demonstrated powerfully in New York City after Hurricane Sandy and in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria.

Privacy and Digital Sovereignty: Your data on a corporate ISP is subject to their logging and surveillance policies. A community-owned network can be designed with privacy-by-architecture, keeping local traffic local and minimizing external data harvesting.

Resistance to Censorship & Shutdowns: Authoritarian regimes often shut down centralized internet access. Mesh networks, with no central switch to flip, are notoriously difficult to censor or disable completely.

Economic Justice: Profits from subscription fees stay within the community, often reinvested into the network or local projects, rather than flowing to distant shareholders. It’s digital localism.

The “How”: Technical Building Blocks

Building a mesh network is more about community organizing than advanced engineering. The core components are:

Hardware: Off-the-shelf, low-cost wireless routers (like those from GL.iNet, Ubiquiti, or TP-Link) that can run open-source firmware. For longer links, directional antennas (like dish or panel antennas) are added.

Software (The Secret Sauce): Proprietary firmware is replaced with open-source operating systems like OpenWrt, which can then be configured with mesh protocols. Dedicated mesh firmware like LibreMesh or QMP (Quic Mesh Protocol) simplify setup, automatically handling node discovery, routing, and network management.

The Mesh Protocol: This is the intelligence of the network. Protocols like B.A.T.M.A.N. (Better Approach To Mobile Adhoc Networking) or OLSR (Optimized Link State Routing) allow nodes to constantly communicate their presence and find the best path for data, without a central controller.

Backhaul: To provide actual internet access, at least one node in the mesh needs a connection to the wider internet—a gateway. This could be a donated business fiber line, a subsidized municipal connection, or even a satellite link. This bandwidth is then shared across the mesh.

The Blueprint: Steps to Building a Community Mesh

Organize the People First: The biggest challenge is social, not technical. Host town halls, identify champions, and form a cooperative or non-profit entity. Define your shared goals and governance model.

Map and Plan: Use tools like Line-of-Sight (LoS) mappers to plan node placement. The goal is to create a dense web of connections, often starting with a “seed” cluster of homes willing to host nodes.

Pilot and Test: Start with a small cluster of 3-5 nodes. Install hardware, flash routers with mesh firmware, and test connectivity. This builds confidence and provides a proof-of-concept.

Scale the Network: Onboard new members through “install parties,” where volunteers help neighbors set up nodes. The network grows organically, strengthening with each new participant.

Maintain and Govern: Establish a maintenance fund and a technical support team (often volunteers). The community must decide on rules: usage policies, fair sharing of backhaul costs, and how to handle expansion.

Real-World Examples: From Berlin to Brooklyn

Guifi.net (Catalonia, Spain): The world’s largest community network, with over 100,000 active nodes. It began in a rural area with no ISP interest and grew into a robust, open-access federation providing internet and local services.

Freifunk (Germany): A federation of over 400 local community networks across Germany. Their motto is “network access for everyone.” They provide free, anonymized internet in neighborhoods and refugee shelters.

Red Hook Initiative Wifi (Brooklyn, NYC): Built after Hurricane Sandy cut off communication, this mesh network provides free internet, local information, and resilience for a historically underserved waterfront community.

NYC Mesh: A volunteer-driven network connecting thousands of households across New York City, offering an alternative to major ISPs with a focus on net neutrality and privacy.

Challenges and Considerations

The Last-Mile/Last-Acre Problem: Getting nodes on buildings requires permission and trust. Rooftop access is key.

Technical Stewardship: Relies on a core group of volunteers, which can lead to burnout. Sustainable models are crucial.

Legal and Regulatory Hurdles: Spectrum regulations vary by country. Most operate in the public, unlicensed spectrum (2.4 & 5 GHz bands), which can get congested.

Performance: A mesh is not a magic bullet for ultra-high-speed gaming. Latency can be higher due to multiple hops, but it excels at providing reliable, functional broadband for communication, education, and work.

The Future: More Than Just Internet

The true potential of community meshes extends beyond basic connectivity. They become platforms for:

Hyperlocal Services: Hosting community message boards, local news servers, or neighborhood safety apps that work even if the wider internet is down.

Environmental Monitoring: Deploying air quality or noise pollution sensors across the network.

A Living Laboratory: A tangible example of a cooperative, peer-to-peer economy in action—a model for reclaiming control over other essential digital infrastructures.

Conclusion

Community mesh networks represent a powerful fusion of appropriate technology and social solidarity. They prove that internet access doesn’t have to be a top-down commodity; it can be a collaboratively built common. While not a panacea, they offer a compelling, resilient, and sovereign model for connectivity—one router, one rooftop, and one neighborhood at a time. In rewiring their own connections, these communities are not just building networks; they are rebuilding a sense of shared agency in the digital age.

OTHER POSTS